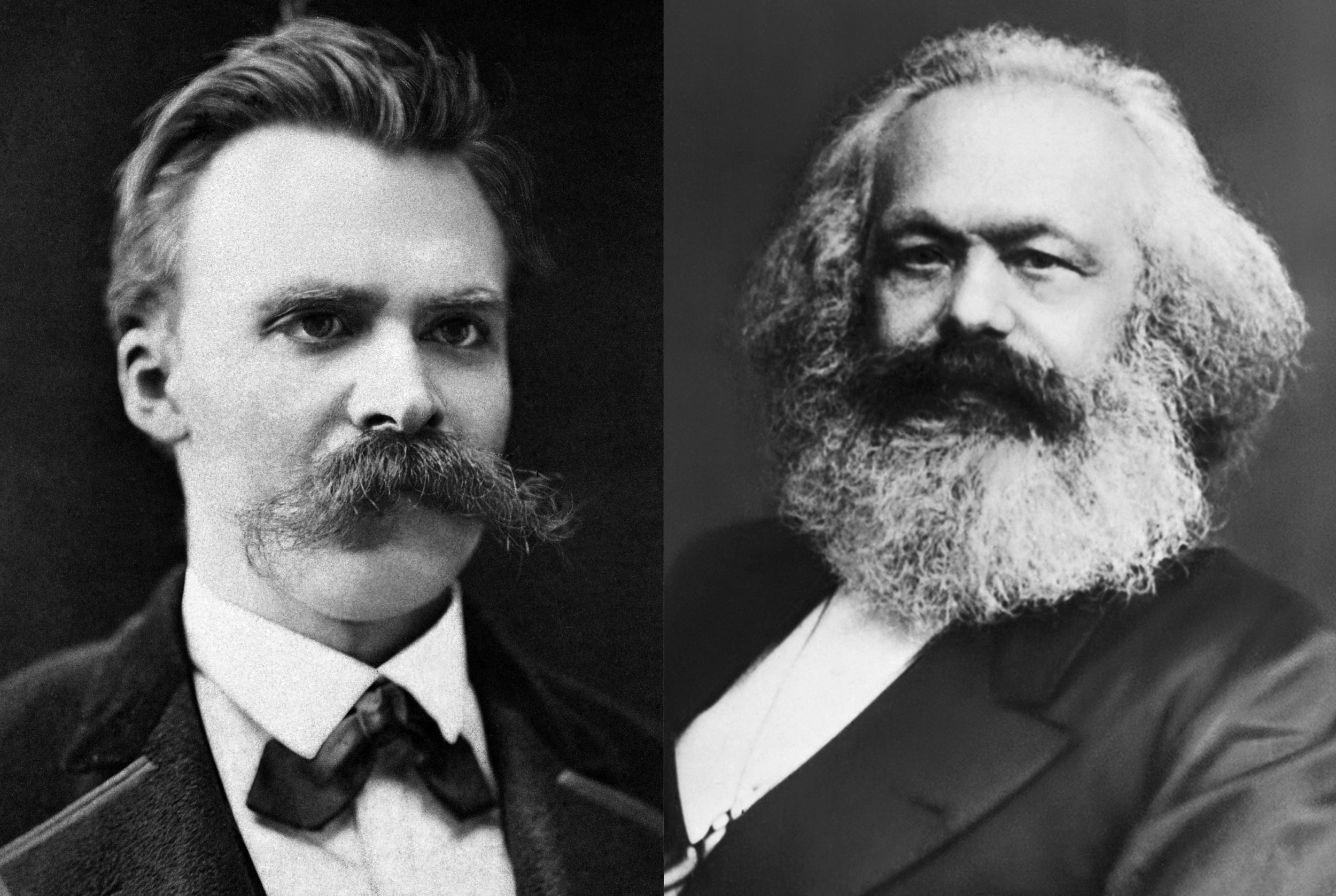

Sometimes the best way to gauge the importance of a classic thinker is to examine how much their ideas have been either oversimplified or manipulated for ideological purposes. Few figures have fallen victim to this phenomenon as much as Friedrich Nietzsche and Karl Marx. These theorists of modernity have been targets of both hagiography and iconoclasm. To make matters worse, their ideas have often been pitted against each other, with each figure supposedly representing opposing ends of the political spectrum. Both these influential thinkers routinely get blamed for events which occurred long after they died and over which they had no control. Marx is wrongly held directly responsible by those on the right for Stalinism. Similarly, Nietzsche gets cursorily dismissed by those on the left for his posthumous cooptation by Nazism. Recently, Domenico Losurdo’s Nietzsche, the Aristocratic Rebel follows in that fashion.[1] Losurdo attempts to portray Nietzsche as inherently antisemitic, despite the fact that Nietzsche explicitly and frequently expressed his own hatred of antisemitism. Losurdo tries to wedge Nietzsche’s thought into a narrow political project, but, in doing so, he overlooks his key insights. By overemphasizing the socio-political context of the time and place in which Nietzsche lived, Losurdo reduces Nietzsche’s philosophy to that context, and the actual content of Nietzsche’s philosophy gets drowned out. Nietzsche’s ideas were radical precisely because they went against the expectations of intellectuals living in his time and place, thus, looking only at Nietzsche’s surroundings causes one to miss his most vital observations.

Luckily, a new work by Jonas Čeika does not succumb to these pitfalls so common in contemporary leftist literature. In How to Philosophize with a Hammer and Sickle, Čeika rescues Nietzsche and Marx from their undeserved fates as caricatures and examines how their ideas are more compatible than have often been depicted. For much of the latter half of the twentieth century, both philosophers’ ideas have been unduly reduced to crude distortions that render Nietzsche as someone mainly concerned with culture and Marx as someone mainly concerned with economics. But both characterizations are obviously inaccurate. While it is unclear if Nietzsche ever read Marx (although he did underline his name in one of his books, so he was aware of him), Nietzsche’s conclusions were reliant on problems he saw within capitalism, just as Marx’s conclusions were fueled by his understanding of the human condition. Čeika mentions early in the book that “the extent to which their irreconcilability has been exaggerated is only one of the many reasons to unite them,” saying that admirers of Nietzsche have been adverse to Marxist philosophy (or, at least, what Marxist philosophy has become in the academy), which has “been made into a closed system, a rigid framework.” This shift makes it necessary to resurrect the human element in Marx—the “Nietzschean aspects of Marx”—that have gone unnoticed.[2] Čeika thus unearths dormant values in each figure’s thought that are useful to a modern emancipatory politics.

Marx and Nietzsche both viewed philosophy as a living and breathing process, not a stagnant, purely scholastic endeavor. Čeika notes that Marx and Nietzsche agree that “one cannot separate philosophy from its practical context and effects, from its uses, its functions, and its goals.”[3] While we use conceptual categories out of necessity to organize a chaotic existence, we have to acknowledge their limitations, such as the impossibility of a wholly bird’s eye view of the world. Recognizing this basic fact has led those who prefer black-and-white categorizations to mislabel Nietzsche as a kind of “postmodern” predecessor, accusing him of relativistic tendencies.[4] This clumsy misrepresentation of Nietzsche obscures the fact that both Marx and Nietzsche rejected the abstract idealism that dominated Western philosophy in their time for its lack of connection to the real, material world. Nietzsche said that the more perspectives we are able to bring into the fold, “the more complete will be our ‘concept’ of the thing, our ‘objectivity.’”[5] “Objectivity,” Čeika notes, “is not the abandonment of all particular perspectives, but the accumulation and amalgamation of perspectives, through which we exercise our ‘active and interpretive powers.’”[6] Marx echoes these views by attacking the reigning Hegelianism of his day, arguing that human consciousness is not determined by some theoretical force or soul, but rather by studying the person as “a natural, corporeal, sensuous objective being.”[7]

It is here in this material body that Marx and Nietzsche place their starting point for philosophy, not in some realm of absolute spirit or forms. The body is not in a permanent state, but it is constantly changing from forces acting upon it and forces it exerts onto the world. History as a whole, then, is dynamic, not “just a collection of dead facts, but the process by which human beings continuously extend their powers, creating and transforming the world.”[8] This view, as Čeika points out, is the central theme of Marx’s “Theses on Feuerbach,” as well as Nietzsche’s Twilight of the Idols.[9] Marx and Nietzsche emphasize that analysis is merely a starting point, and that analysis alone is not sufficient for any transformative philosophy. This concept put them both at odds with academia. Nietzsche’s impassioned writing style was incompatible within the growing field of analytic philosophy, which stressed maintaining a mathematical-like disinterestedness and preferred “humanistic” methods like Nietzsche’s be relegated to the literary or poetic realm.[10] Marx’s ideas were also deemed too radical. One reason their philosophies did not fit well within the academy stems from the institutionalization of the university beginning during the nineteenth century. Philosophy itself was no longer a vigorous and metamorphic activity, but instead became an instrument of academic specialization that competed with the hard sciences through the alliance between the university and the state.[11] But considering Nietzsche and Marx’s overall impact, the fact they were spurned by the academy seems only to confirm their thesis that any philosophy worth pursuing cannot take place in an armchair.

Working outside the typical academic constraints meant that Marx and Nietzsche had a clearer understanding of the intimate relationship between one’s labor and one’s passions. Čeika observes that being free of bourgeois controls allowed them “to view things in their interconnections, their interdependent relations, even those which transcended disciplines.”[12] Their audience, then, was the modern person from all walks of life, not just a handful of professors on a tenure committee. They did not merely write theory for its own sake—they saw theory as a vehicle for the liberation of humankind. To that end, both figures sought to explain the consequences of modernity itself. Čeika argues that “Marx and Nietzsche are critics of modernity par excellence,” and their philosophical approach “is nothing like Plato’s or John Rawls’s, who inquire beyond time and place, beyond history, in an attempt to discover eternal and absolute social laws or ideals. Instead, they historicize, excavate, examine social symptoms, and dive into the depths of the modern social condition, always from the standpoint of immanent practice—they are aware of how their thought itself is sharpened by the conditions which they analyze.”[13]

Nietzsche’s famed proclamation that “God is dead” meant that modern science, particularly the insights derived from evolution, destroyed the theistic premise that provided a basis for all Western thought; therefore, Western philosophy from Plato to Hegel had to be reimagined in light of modernity.[14] Even though the West no longer had a metanarrative, Nietzsche argued that the ascetic ideal, which Christianity had embedded in the Western mindset for centuries, enslaved humanity by internalizing guilt, so even though the world had become secular, the drive to moralize remained. Similarly, Marx’s assertion that religion is the “opiate of the people” echoes Nietzsche’s critique of the ascetic ideal. Marx was not criticizing the religious or cultural beliefs of individuals so much as he was criticizing the institution of the Church that had dominated people’s minds for centuries. For Marx, religion represented the “sigh of the oppressed creature,” an illusory kind of spiritual balm birthed out of desperation to soothe the material suffering caused by the oppression of the ruling classes, for whom the Church acted as an ideological arm.[15]

Core to both Nietzsche and Marx’s thought is the structural social and economic changes brought about by capitalism. Today’s anti-Nietzscheans have attempted to portray Nietzsche’s politics as being inherently elitist or reactionary, usually pointing to his comments on democracy, aristocracy, and socialism. These positions not only completely misunderstand Nietzsche’s meaning, but they ignore the fact that Marx had very similar critiques on liberal democracy and the socialism of his day. In other words, to dismiss Nietzsche as irrelevant to the left means one would have to dismiss much of Marx’s work in kind. As Čeika points out, “the reason Nietzsche posited an ‘aristocracy’ as his future ideal was because the aristocracy is a pre-modern phenomenon, and therefore, like Nietzsche himself, exempt from both labor and commerce. The ‘aristocracy’ was Nietzsche’s way of positing a socio-political element beyond capitalism.”[16] A close reading of Nietzsche’s works reveals that he despised capitalism, decrying it as one of the “crudest and most evil forces” that demands a kind of bourgeois idolatry and “holds sway over almost everything on earth,” adding that “the educated classes and states are being swept along by a hugely contemptible money economy.”[17] Nietzsche elaborated on how capitalism creates workers who are “used, and used up, as a part of a machine,” suggesting that they “protest against the machine, against capital.”[18]

If Nietzsche hated capitalism so much, why did he also dislike socialism? The answer is that “socialism” as he understood it did not resemble any form of Marxist socialism. Rather, the versions of socialism Nietzsche spoke against were the same ones Marx denounced. Socialism, as Nietzsche understood it, was just another moral system, one that elevated abstract ideals of rights, justice, or equality—not too dissimilar from the European liberal traditions of the time. But there is a reason Marx declared that “communists do not preach morality at all!”[19] It is not that Marxists do not endorse the concept of equality—the problem is that trying to establish rights or justice through a legal or moral system does not address the fundamental structural and material problem that capitalism presents. A socialist in the Marxist tradition is not satisfied merely trying to fix social problems by working within a capitalist system—Marxists ultimately seek to abolish capitalism altogether. In his Critique of the Gotha Programme, Marx elaborated on the feebleness of egalitarianism as a political program, saying that “right, by its very nature, can consist only in the application of an equal standard; but unequal individuals (and they would not be different individuals if they were not unequal) are measurable only by an equal standard insofar as they are brought under an equal point of view, are taken from one definite side only… everything else being ignored,” adding that “right can never be higher than the economic structure of society.”[20] Reflecting the ideas of his philosophical partner, Friedrich Engels summed up why Marxists do not frame their goals in terms of egalitarianism, arguing that “the concept of a socialist society as a realm of equality is a one-sided French concept deriving from the old ‘liberty, equality, fraternity,’ a concept which was justified in that, in its own time and place, it signified a phase of development, but which, like all the one-sided ideas of earlier socialist schools, ought now to be superseded, since they produce nothing but mental confusion, and more accurate ways of presenting the matter have been discovered.”[21]

The commonalities shared by Marx and Nietzsche still hold significance for the left today. Both emphasized materialism over idealism; both rejected the various strands of political economy and moralism of their day; both abhorred what capitalism does to education, culture, and the individual. Most importantly, both figures sought to overcome these oppressive systems and saw the possibility of true human emancipation. While the twenty-first century world looks different than the world in the nineteenth century, the same structures that Marx and Nietzsche rallied against still dominate. That reality makes their combined philosophies exceptionally relevant. Like Čeika eloquently points out, “Socialism and life-affirmation are not fantasies or ideals that we dream up or pluck from the sky to then impose onto the world. Rather, they are real immanent historical possibilities, made possible, and even necessary, by already-existing conditions. The tendencies which move towards socialism and life-affirmation already exist, just as the tendency towards the blooming of a flower already exists in its seed, and there is not a day on Earth that individuals do not struggle to extend them. At the same time, there is nothing inevitable about such development, as countertendencies always threaten to crush the seed before it grows. All we need is to kindle the tendencies of affirmation, to further them, and unleash their unfolding until they realize their most joyful potential.”[22]

Footnotes:

[1] Domenico Losurdo, Nietzsche, the Aristocratic Rebel: Intellectual Biography and Critical Balance-Sheet (Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2019). Losurdo tries to formulate his arguments about Nietzsche based largely on speculation, looking at Nietzsche’s circle of friends, unpublished notes and letters taken out of context, and documents that are known by Nietzsche scholars to be manipulated for political purposes. Losurdo attempts to obscure his own ideological biases by burying Nietzsche’s actual words beneath many pages of seemingly detailed research, suggesting that, despite Nietzsche’s many utterances otherwise, Nietzsche was using “coded” language to disguise his antisemitism. He also ignores that the socialism Nietzsche was resistant to was the same socialism that Marx was resistant to, which causes him to misunderstand what Nietzsche meant when he discusses his particular concept of “aristocracy.” Essentially, Losurdo’s entire premise rests upon a series of faulty inferences. Unfortunately, the attempt to portray Nietzsche as antisemitic despite historical evidence otherwise has become fashionable. Don Dombowsky, Malcolm Bull, and other anti-Nietzscheans have tried to take down Nietzsche as a figure who has something to offer the left. For a good summary of why this approach is flawed, see Brian Leiter’s review of Robert Holub’s 2015 book Nietzsche’s Jewish Problem: Between Anti-Semitism and Anti-Judaism: Brian Leiter, “Nietzsche’s Hatred of ‘Jew Hatred,’” The New Rambler, December 21, 2015. For a brief discussion of this trend within academia, see also: Ross Wolfe, “Twilight of the Idoloclast? On the Left’s Recent Anti-Nietzschean Turn,” The Charnel-House, 2013.

[2] Jonas Čeika, How to Philosophize with a Hammer and Sickle: Nietzsche and Marx for the Twenty-First Century (London: Repeater Books, 2021), 4.

[3] Ibid., 9.

[4] The slapdash use of the word “postmodern” is conveniently thrown around on both the left and the right as a poor substitute for “relativism,” usually by those unfamiliar with the fact that the concept of relativism is both ancient and complex, having little to do with the historically-situated concept of postmodernism. Further, the term “postmodern” is better understood as an umbrella term that houses a wide range of philosophical concepts under it, and “postmodernism” is less a unified philosophy and more an analysis of a contemporary condition. For a simplified explanation of the various meanings associated with the term, see: Shalon van Tine, “Postmodernism, Explained,” Myth & Mayhem, June 22, 2020.

[5] Friedrich Nietzsche, Nietzsche: On the Genealogy of Morality and Other Writings, trans. Carol Diethe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006, orig. 1887), 87.

[6] Čeika, How to Philosophize, 11.

[7] Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, trans. Martin Milligan (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1959, orig. 1844), 69.

[8] Čeika, How to Philosophize, 30.

[9] See generally: Karl Marx, “Theses on Feuerbach,” in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The German Ideology (New York: Prometheus Books, 1998, orig. 1845); Friedrich Nietzsche, The Twilight of the Idols, or, How to Philosophize with a Hammer, trans. R. J. Hollingdale (New York: Penguin Books, 1990, orig. 1889).

[10] Nietzsche first studied philology, the study of classical languages, literatures, and religion that would later become the basis for the variety of disciplines under the banner of the “humanities.” Philosophy as an academic discipline, on the other hand, developed along a separate path (even though they overlap, of course). Given his educational background, it made some sense that Nietzsche’s approach to philosophy seemed, to his detractors, a better fit in the wider humanities than in an analytic philosophy department since the study of philosophy in the modern university setting becomes stripped of its radical potential. For a closer look at the development of these fields, see: James Turner, Philology: The Forgotten Origins of the Modern Humanities (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

[11] Nietzsche expanded on how the modern university system deprives the student from a quality education in a series of lectures released under the misguided title Anti-Education, aptly pointing out how the university system turns education into an instrument for the student to get “as much knowledge and education as possible—leading to the greatest possible production and demand,” adding that the university system demands “a rapid education, so you can start earning money quickly.” He notes, “Here we have Utility as the goal and purpose of education, or more precisely Gain: the highest possible income,” emphasizing that higher culture “is tolerated only insofar as it serves the cause of earning money.” Some have viewed these statements as evidence of Nietzsche’s supposed “elitism,” but that conclusion misses the important point that Nietzsche was making about the decay of higher education, a point that has proved to be even more relevant today than in his own time. For more on Nietzsche’s views on the modern educational system, see: Friedrich Nietzsche, Anti-Education: On the Future of Our Educational Institutions, trans. Damion Searls, ed. Paul Reitter, Chad Wellmon (New York: NYRB Classics, 2015, orig. 1869), 20–21. For a relevant overview of the history behind the development of the social sciences fields within the academy, see also: Immanuel Wallerstein, “Historical Origins of World-Systems Analysis: From Social Science Disciplines to Historical Social Sciences,” in World-Systems Analysis (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), 1–22.

[12] Čeika, How to Philosophize, 45.

[13] Ibid., 50.

[14] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Vintage Books, 1974, orig. 1882), 181. Nietzsche accepted most of Charles Darwin’s claims about evolutionary theory, even though he did not think that evolution explained all aspects of human aesthetics. Still, Darwin had a profound impact on Nietzsche’s thought, and the fact that humans developed from natural processes rather than a divine creator is key to understanding why Nietzsche saw most philosophical positions before modernity as outdated. For more on Nietzsche and Darwin, see: H. James Birx, “Nietzsche and Evolution,” Philosophy Now, October 2000.

[15] Karl Marx, Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, trans. Annette Jolin and Joseph O’Malley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970, orig. 1843), 131.

[16] Čeika, How to Philosophize, 72.

[17] Friedrich Nietzsche, Untimely Meditations, trans. R. J. Hollingdale, ed. Daniel Breazeale (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997, orig. 1876), 148–150.

[18] Friedrich Nietzsche, Daybreak, trans. R. J. Hollingdale, ed. Brian Leiter, Maudemarie Clark (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997, orig. 1881), 127.

[19] Marx and Engels, The German Ideology, 264.

[20] Karl Marx, Critique of the Gotha Programme (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1970, orig. 1875), 26.

[21] Friedrich Engels, quoted in August Bebel, My Life (New York: Baker & Taylor Co., 1911, orig. 1875), 178.

[22] Čeika, How to Philosophize, 256.

By Shalon van Tine