Originally published in Left Voice | March 3, 2022

Republished in Carcará Weekly | March 4, 2022

March is Women’s History Month, and there is no better time to watch some outstanding films made by women directors. Directors like Agnès Varda, Julie Dash, or Chantal Ackerman might not be household names, but they have made an indelible imprint on hundreds of films and filmmakers that came after them. From the feminist psychedelia of Daises to the anti-colonialist, coming-of-age drama Chocolat, these are eleven films directed by women internationally you might not have heard of but would not want to miss.

Meshes of the Afternoon (United States, 1943)

Directed by Maya Deren with her then husband, Alexander Hammid, Meshes of the Afternoon presents an eerie, surrealistic dreamscape that vividly captures the sensation of one’s internal anxieties.[1] Film scholar Maureen Turim notes how Deren locates the film “inside the home, inside the artist’s mind, and inside the unconsciousness.”[2] Frequently acknowledged as one of the most innovative movies in experimental cinema, this short film captures Deren’s affinity for movement and space using arresting imagery in what film scholar Thomas Schatz calls a “poetic psychodrama.”[3] Homages to the haunting images in Meshes can be seen in everything from the films of David Lynch to the music videos of Kristin Hersh.[4]

Born in Ukraine, Deren immigrated with her family to the United States to escape anti-Semitism. In college, she studied journalism and political science, and she became an active Trotskyist, giving lectures and organizing with the Young People’s Socialist League.[5] She later earned a master’s degree in literature and moved to Greenwich Village to become a secretary for famed choreographer Katherine Dunham, which fueled her interest in dance. After moving in avant-garde circles with well-known artists like John Cage and Anaïs Nin, Deren began experimenting with film and blended her wide-ranging interests in French Symbolism, Haitian Vodou, and Gestalt psychology into mesmerizing movies.[6] Sixty years after her death, Deren’s experimental cinema continues to inspire groundbreaking filmmakers today.

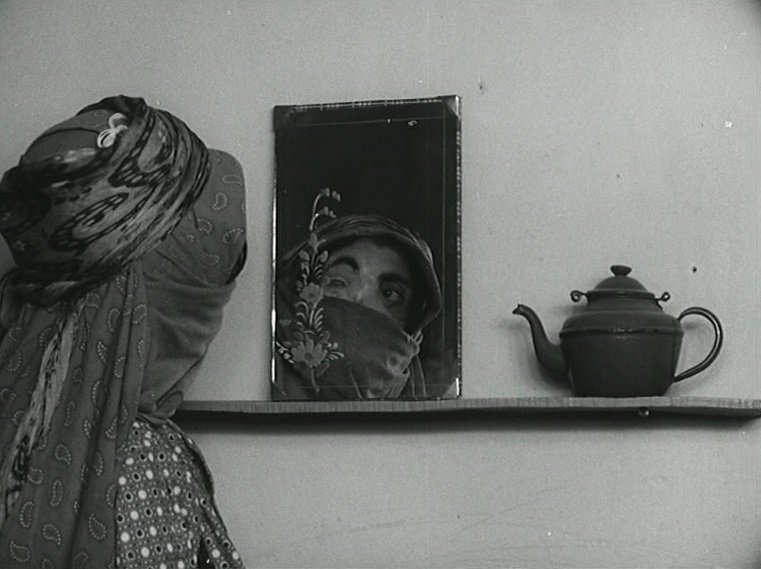

The House Is Black (Iran, 1963)

Forugh Farrokhzad is remembered as one of the leading Iranian poets of her day, but The House Is Black is the only film that she ever directed. Her criticisms of the social injustices faced by Iranians under the shah, as well as her progressive views on gender, led authorities to ban her poetry after the Iranian Revolution.[7] Farrokhzad said that “what is important is humanity, not being a man or a woman. If a poem can get to that point, it is no longer connected with its creator, but with a world of poetry.”[8]

This short documentary functions as a visual poem itself and focuses on the daily lives of people living in a leper colony. Farrokhzad juxtaposes Christian and Islamic scriptures along with her own poetry over jarring images of those shunned from society because of their disease. The rhythms of the film mimic the meter common in Persian poetry, and the inclusion of Koranic and Biblical passages overlaid on scenes of human suffering create a metaphor for social strife in Iranian culture. Farrokhzad forces viewers to confront that which they would turn away from, as the voiceover in the beginning of the film explains: “There is no shortage of ugliness in the world. If man closed his eyes to it, there would be even more.”[9]

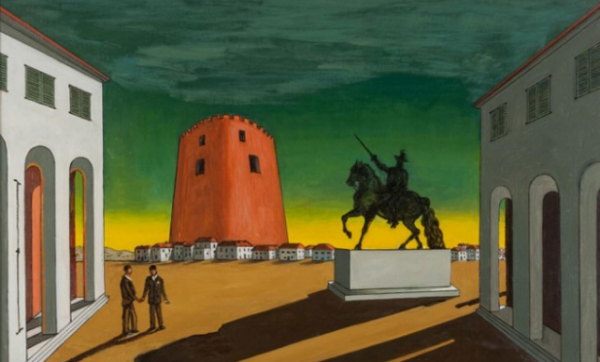

Daisies (Czechoslovakia, 1966)

Raised in a strict Catholic household in Czechoslovakia, Věra Chytilová developed an aversion to the conservative oppression of women. Having to fight her way into a male-dominated film school reinforced this hostility toward patriarchal systems.[10] These experiences are evident in her most celebrated film, Daisies, which so offended the government that it banned the movie and prohibited Chytilová from making any more films in her home country. Despite its censorship, Daisies would prove to be a landmark in feminist cinema.[11]

The film follows the zany adventures of two teenage girls, both named Marie, as they pull pranks on polite society and wreak havoc wherever they roam.[12] The Maries dress provocatively and challenge the traditional conventions of behavior that were expected of young women at the time by doing a series of rebellious acts, such as acting drunk in public and conning older men into buying them expensive dinners. Chytilová litters the film with anti-patriarchal symbols, like having the Maries chop up phallic sausages with scissors or making fun of female stereotypes by having them act like mindless marionette puppets. The film also compares the repression of female individuality with the repression of creative expression. Food is a recurring motif in the movie, as the girls constantly waver between being hungry or wasting food, culminating in a wild scene in which they annihilate a fancy banquet in an epic food fight.

In addition to its social commentary, Daisies is considered innovative for its editing and storytelling method, which integrated novel techniques like photo collage and predated the kind of style that would later become core to the punk aesthetic. By taking these madcap characters to absurdist extremes, Chytilová created one of the most confrontational and visually stimulating films in the feminist canon.

Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (Belgium, 1975)

A typical movie jumps from one dramatic scene to the next and cuts out all the mundane stuff in the middle. In Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, however, all the ordinary rituals of everyday life are left in yet build to a climactic ending. The film follows a widowed mother over the course of three days as she performs the most banal tasks: making coffee, cooking dinner, washing dishes, taking a bath, changing sheets, and taking care of her teenage son.[13] The camera stays fixed on her every movement so the viewer is forced to take in all the little things about daily life that would usually go unnoticed. To make money, she receives male visitors in the afternoons while her son is in school. These sexual transactions are treated the same way she treats every other household task, as just another step in her monotonous cycle.

But then one day the smallest change happens: she wakes up a little earlier than usual. What would seem like a trivial change to her normal pattern actually sets off her unraveling. Not knowing what to do with the spare time, she sits and fidgets, and even though she remains silent, the viewer can sense the overwhelming anxiety she feels at having lost a sense of control over her meticulous routine. Gradually, she begins to make tiny mistakes that disrupt her highly disciplined process: she drops a spoon, she leaves the lid off a jar, she overcooks the potatoes, she leaves a few strands of her hair uncombed. These subtle errors eventually culminate in the movie’s shocking ending.

Film scholar Ivone Margulies notes that Jeanne Dielman “engages broadly with a feminist problematic, one that takes into account a woman’s alienation, her labor, and her dormant violence.”[14] The slightest upset in the mother’s routine uncovers the oppressive domestic sphere that she has adapted to. She is surrounded by unspoken patriarchal conventions as the men in her life use her in a coldly functional way. Her son barely acknowledges her existence and just depends on her for sustenance. When she is filmed interacting with her clients, her head is cut off in the framing, suggesting that these men merely exploit her for her parts rather than consider her a whole person. When Akerman films her doing chores, she is framed within the domestic space as if she is confined by it. Her liberation comes when she can break free of her domestic captivity — but that leads to a devastating conclusion. When the movie came out, film critic Louis Marcorelles said that Jeanne Dielman was the “first masterpiece of the feminine in the history of the cinema.”[15] Akerman claimed that she made “a love film for my mother,” and she insisted that at least 80 percent of the production crew be composed of women.[16] Indeed, the movie proves to be a sympathetic portrayal of the multifaceted, often hidden layers that embody many facets of womanhood.

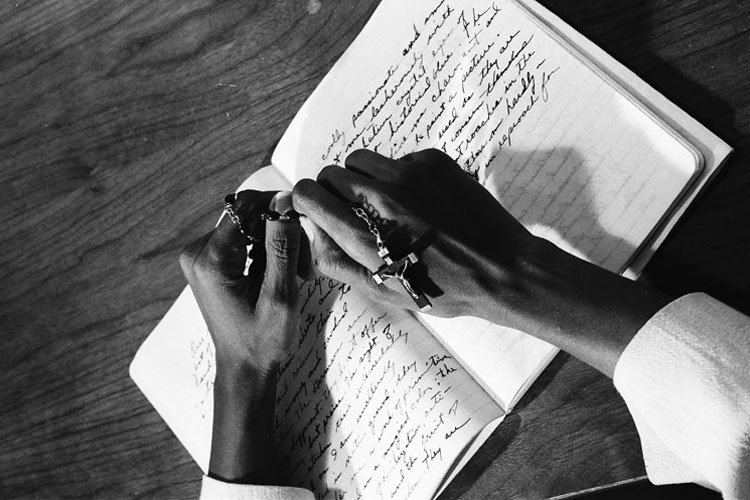

Diary of an African Nun (United States, 1977)

When Beyoncé released her 2016 visual album Lemonade, many critics immediately noticed the similarities to Julie Dash’s 1991 film Daughters of the Dust, one of the first movies about the Gullah people in the low country region of the Sea Islands off South Carolina and Georgia.[17] Dash emerged from the L.A. Rebellion scene, a collective of African American filmmakers in the 1970s and 1980s who challenged the blaxploitation style in Hollywood at the time and instead created humanist films with more complex and socially dynamic characters (most remembered of these is Charles Burnett’s 1978 picture Killer of Sheep).[18] Daughters centers on conflicts between the past and the present, tradition versus progress, and ancient versus modern.[19] These themes show up over a decade earlier in Dash’s short film Diary of an African Nun.

Based on a story by Alice Walker, Diary transpires inside the thoughts of a Ugandan nun who struggles to find her place between her devotion to Christianity and her yearning toward her African religious roots.[20] In her diary, she notices how Westerners see her as an example of progress overcoming paganism, observing how they consider her “a work of primitive art, housed in a magical color; the incarnation of civilization, anti-heathenism, and the fruit of a triumphing idea.”[21] She is first shown composed and contemplative, covered from head to toe in an all-white habit. But as she removes each piece of her garb, the visual contrast between her dark skin and the white robes becomes clearer, and as more of her body is revealed, so too is her true self. She becomes noticeably frustrated and begins questioning her religious path while longing to participate in the religion of her ancestors. During this highly ritualized undressing, she looks out her window and hears drumming, smells cooking meat, and envisions the singing and dancing that precedes copulation — all the while confronting Christ in her prayers for being silent, passionless, and intangible: “Must I still ask myself whether it was my husband, who came down bodiless from the sky, son of a proud father and flesh once upon the earth, who first took me and claimed the innocence of my body? Or was it the drumbeats, messengers of the sacred dance of life and deathlessness on Earth? Must I still long to be within the black circle around the red, glowing fire, to feel the breath of love hot against my cheeks, the smell of love strong about my waiting thighs?”[22] As critic Eva Darias-Beautell has pointed out, the nun “is trapped between the law of the father — the patriarchal system of Catholicism — and that of the mother — her Ugandan tribe, a natural vessel of love and life.”[23] Dash’s film version of this narrative beautifully captures these tensions and brings Walker’s story to life.

The Ascent (Soviet Union, 1977)

Directed by Larisa Shepitko, The Ascent is set in Nazi-occupied Belarus during World War II, although it is not really about the war itself. There are no battle scenes or dramatizations of historical events. Instead, the movie uses the war as a backdrop to explore the theme of survival. The story follows two Soviet partisans who brave the elements to find food and supplies for their group. Captured by the Germans, the men are faced with the moral dilemma of having to choose between staying true to their cause or saving their own lives. Shepitko filmed the movie in the dead of winter to re-create the harsh living conditions that Soviets would have faced during the war. Nature acts as an oppressive force, and the main characters battle external challenges (snow, famine, fascists) as well as internal struggles (loyalty, friendship, ideology). In one depressing scene, one of the captured prisoners is interrogated by the police. Trying to stand by his ideals, he tells the officer that “some things matter more than skin,” but the officer replies unaffectedly, “rubbish.”[24]

Shepitko made her actors stare directly into the camera and used a nontraditional style of framing, giving the movie an unsettling feeling that forces viewers to feel the suffering of the characters and the bleakness of their situation. Cultural critic Susan Sontag declared that The Ascent was “the most affecting film about the horror of war.”[25] The film was almost banned by censors due the inclusion of Christian symbolism, but luckily Shepitko’s husband, filmmaker Elem Klimov, invited Pyotr Masherov, who had been a Soviet partisan himself, to view the film. Masherov was so moved by the picture that the film was accepted without revisions.[26] Unfortunately, it would be the last film Shepitko would make, as she died (along with five other members of her crew) in a car accident just two years later.[27] With striking and poetic imagery, Shepitko’s film is now considered a Soviet masterpiece because it demonstrated how endowing misery with meaning is a crucial part of the universal human experience.

Vagabond (France, 1985)

Agnès Varda’s Vagabond begins with an image of a dead woman in a ditch covered in frost. As the police wrap up her body, Varda explains in a voiceover that no one claimed the body, and nobody really knew who she was. The film then goes back in time to follow the woman on her journey and periodically interviews characters she encountered along the way.[28] Even though the movie is fictional, Varda films the story like a documentary. The audience learns that her name is Mona, and she did not like school or work, so she decided to wander the French countryside alone. Besides those basic facts, the viewer does not learn of any deeper psychological or political motivation for her self-imposed homelessness. As far as anyone can tell, she does not have one. She is simply a drifter.

Throughout her wanderings, she meets a variety of people: a professor, a maid, a goatherd, a trucker, a vineyard worker. Mona is not a completely sympathetic character: she is dirty, she is ungrateful at times, she is self-serving, she is sometimes rude. But the way each character reacts to Mona tells the bigger story. As writer Andrea Kleine notes, Mona alternates between representing “a blank slate, a whore, a romantic, a symbol of freedom, a nuisance, a protégé, or easy pickings.”[29] It is how others see Mona — a figure who lives completely outside societal norms — that says more about society than Mona herself. Varda became interested in the topic of women vagrants after picking up a hitchhiker and learning more about the rise in homelessness among young women in the 1980s.[30] She pointed out that “we all have inside ourselves a woman who walks alone on the road. In all women, there is something in revolt that is not expressed.”[31]

Chocolat (Cameroon/France, 1988)

Directed by Claire Denis, Chocolat takes a glimpse into the life of a small household in French-controlled Cameroon in 1957, just three years before the country declared its independence.[32] Loosely inspired by Denis’s own experiences growing up in Africa, Chocolat portrays the effects of colonialism on the region through the eyes of a child. The story centers on the wife of a local administrator and her daughter, France, who befriends their head African house servant, Protée.[33] Protée teaches France miniature life lessons by using riddles and subtle gestures in a way that makes adult concepts understandable to a young girl. In one poignant scene, a hyena has killed some of the domestic animals, and Protée silently takes the blood of one of the dead creatures and rubs it onto France’s hands, creating a powerful symbol that illustrates to her and to the viewer the nature of French colonialism. In another powerful scene, Protée allows France to burn her hand on a pipe by acting as if it does not burn his own hand (even though it does), leaving both their hands scarred. Film scholar Cornelia Ruhe has pointed out that the shared scarring “shows both their identities as marked by the experience of colonialism.”[34]

Throughout the film, multilayered tensions emerge between Protée and France’s mother, Aimée. There is a clear sexual attraction between them, but there is also an unspoken awareness of the unevenness of their class and racial positions. When Aimée takes advantage of her position of power, Protée responds with a composed dignity that works as a metaphor for the resilience of the colonized in the long fight for freedom from their oppressors. When some unexpected guests arrive, their presence exposes much of the tacit power struggles within the household, which acts as a parallel between the larger colonial struggles happening at the time. At one point, France asks her father to explain what a horizon is. He describes it as a line one can see but does not actually exist, which provides viewers with a verbal description of what they see in the film: undeclared but actual power divisions between the master and the slave, between the colonizer and the colonized. As film scholar William Vincent explains, the film presents “a set of oppositions — black-white, African–non-African, past-present, north-south, male-female, colonizer-colonized — and asks whether they can be transgressed, by transgression reconciled, and by reconciliation fused.”[35] By telling the story through the perspective of a child, Denis toys with these overlapping tensions and makes compelling political statements without ever becoming heavy-handed.

Monsoon Wedding (India, 2001)

Directed by Mira Nair, Monsoon Wedding is a tale of two interwoven love stories: an arranged marriage between two members from upper-class Indian families and a touching romance between two members from the lower classes. It is also a story about the nuances of familial love and the complications that money brings into family relations.[36]

As a longtime activist, Nair uses the power of film to shed light on the complexities of the human experience, saying that “the screen must reflect the multiplicity of the world we live in.”[37] She set up Maisha Film Lab, a nonprofit mentorship program based in Uganda that helps nurture the creative abilities of aspiring African filmmakers and journalists so they can tell their stories to the world. Nair also used the profits from her popular 1988 film Salaam Bombay to fund the Salaam Baalak Trust, another nonprofit organization that provides education, healthcare, and career training for Indian street children.[38] Understanding the impact that cinema can have, Nair weaves together clashes between tradition and modernity, men and women, parents and children, and the upper and lower classes into relatable humanistic tales that are packed with emotion and chaos, but also full of heart.

The Headless Woman (Argentina/Spain, 2008)

Directed by Lucrecia Martel, The Headless Woman begins with a wealthy woman named Véro driving her car down a winding road. She looks away for a couple seconds to pick up her cell phone when suddenly she hits something — or someone. Jolted and confused, she looks around but sees only the body of a dead dog in her rearview mirror. There is, however, a mysterious child-size handprint on her car window. She drives away, but the incident haunts her. She becomes convinced that she has committed manslaughter, but after expressing her concerns to her husband, her family encourages her to forget the incident, even going so far as to remove evidence of the x-ray she received after the accident.

Throughout the film, clues pop up here and there that suggest that she did indeed kill a child, and Véro wavers between feeling disoriented and guilty. By the end of the story, Véro has suppressed her culpability sufficiently enough to go about her life as normal. When finally confronted with overwhelming evidence — a crew pulling a dead body from a pipe near the road where the accident occurred — Véro and her family purposely ignore it and instead merely roll up the car windows to avoid the putrid stench.[39]

Martel intended her film to serve as an allegory for Argentina’s “Dirty War,” a period in the late 1970s and early 1980s when right-wing death squads (as part of the U.S.-backed “Operation Condor” campaign) attempted to stamp out anyone with socialist associations. Historians estimate that up to 30,000 Argentinians went missing during this time, many of whom were journalists, students, and even children.[40] Véro represents the collective guilt of the bourgeoisie who turned their eye away from the atrocities happening in their own country. These political realities are portrayed in the film through the social decay that happens all around Véro and her peers: polluted water, hepatitis outbreaks, widespread dental problems. And the incestuous nature of Véro’s family appears to signify the bourgeoisie rotting from within its own ranks. This class distinction reveals itself in the way Véro engages with the indigenous workers who are shown regularly fixing things in Véro’s environment. In one important scene, Véro hides in a public bathroom to cry, but when a darker-skinned attendant approaches her, she simply addresses him like a servant and informs him of the broken sink. As writer Phoebe Chen notes, the movie “consistently reminds us that these (mostly white) on-screen figures can’t escape their social and bodily interdependence, that they rely on countless others to exist the way they do.”[41] With great subtlety, Martel puts the viewer into the mind of a woman going mad, largely from her own complicity.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire (France, 2019)

Set in late eighteenth-century France, Portrait of a Lady on Fire tells the story of a brief love affair between two women: Héloïse, the daughter of a countess who is being forced to marry a wealthy Milanese man, and Marianne, a painter hired to complete Héloïse’s portrait for her betrothed. In an effort to resist marriage, Héloïse refuses to have her portrait painted. Marianne is instructed to pretend that she was hired as her walking companion, but she is supposed to construct the painting based on her observations of Héloïse during their daily interactions. When Marianne completes the portrait and tells Héloïse the truth about her purpose there, Héloïse rejects the painting as a poor rendition of her, but agrees to sit for Marianne so that Marianne can paint her properly. With the doors of honest communication now opened, the two develop a deeply intimate relationship.

This narrative, however, is so much more than a typical love story. Director Céline Sciamma said she intended the movie to be a “manifesto about the female gaze.”[42] Indeed, the act of seeing and being seen saturates the entire film. As an artist, Marianne’s livelihood depends on the act of observing, but Héloïse turns this convention around on Marianne, mentioning at one point, “If you look at me, who do I look at?”[43] The conflict between the artist and the subject in Portrait is strikingly similar to Ingmar Bergman’s portrayal of this same kind of tension between two women in his masterful 1966 film Persona.[44] What is interesting about the concept of the gaze in Portrait compared to other films is that there is no male gaze — it is a film about how women see other women. Yet not having men around does not free these characters from their traditional societal roles. As writer Rachel Syme notes, even without men present, the movie “depicts the myriad ways in which the patriarchy constricts the lives of its female protagonists.”[45] In one poignant scene, for instance, Marianne tries to convince Héloïse that marrying a wealthy man is a lucky fate. But Héloïse sharply reminds her that she has no freedom of choice at all and would rather be back at the convent where she was raised because at least that community was egalitarian. Héloïse’s own sister committed suicide so she would not be forced into marriage. While Marianne seemingly has more independence than Héloïse, even though she comes from a lower class, her existence as a woman artist is possible only because she stands to inherit her father’s art studio. She even has to use a male name when submitting her work for exhibition. In another important scene, the two women help the household maid Sophie have an abortion, and they draw the event for posterity.

These bits of the story only scratch the surface of Sciamma’s artful masterpiece, however. Much more could be said about Sciamma’s allusions to the mythic tale of Orpheus and Eurydice, her creative use of music, and her realistic use of natural lighting that captures the setting of the time (akin to Stanley Kubrick’s 1975 period piece Barry Lyndon).[46] But describing Portrait in too much detail is an injustice. Rather, viewers of Sciamma’s film would do better to become absorbed in the story and experience firsthand the revolutionary power that art can have, both inside and outside the film.

Footnotes:

[1] Meshes of the Afternoon, dir. Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid (New York: Kino Classics, 1943), film.

[2] Maureen Turim, “The Ethics of Form,” in Maya Deren and the American Avant-Garde, ed. Bill Nichols (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 84.

[3] Thomas Schatz, Boom and Bust: American Cinema in the 1940s (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 450.

[4] John David Rhodes, Meshes of the Afternoon (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 110–11.

[5] Jonas Mekas, “A Few Notes on Maya Deren,” in Inverted Odysseys: Claude Cahun, Maya Deren, Cindy Sherman, ed. Shelley Rice (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999), 164.

[6] Sally Berger, “Maya Deren’s Legacy,” in Modern Women: Women Artists at the Museum of Modern Art, ed. Cornelia Butler and Alexandra Schwartz (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 301–5.

[7] Elton L. Daniel and Ali Akbar Mahdi, Culture and Customs of Iran (Westport: Greenwood Press, 2006), 81–82.

[8] Sholeh Wolpe, Sin: Selected Poems of Forugh Farrokhzad (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2007), xxvii.

[9] The House Is Black, dir. Forugh Farrokhzad (Tehran: Golestan Films, 1963), film.

[10] Christina Newland, “In Praise of Daisies,” Little White Lies, December 5, 2017.

[11] Peter Hames, The Czechoslovak New Wave (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 151.

[12] Daisies, dir. Věra Chytilová (Prague: Central Films, 1966), film.

[13] Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, dir. Chantal Akerman (Brussels: Paradise Films, 1975), film.

[14] Ivone Margulies, “A Matter of Time: Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles,” Criterion, August 17, 2009.

[15] Lieve Spaas, The Francophone Film: A Struggle for Identity (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), 27.

[16] Gwendolyn Audrey Foster, Identity and Memory: The Films of Chantal Akerman (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003), 78.

[17] Katherine McLaughlin, “Family, Pride, Power: Behind the Groundbreaking Movie That Influenced Lemonade,” Vice, May 31, 2017.

[18] Allyson Field, Jan-Christopher Horak, and Jacqueline Najuma Stewart, “Emancipating the Image: The L.A. Rebellion of Black Filmmakers,” in L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema, ed. Allyson Nadia Field et al. (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015), 1–3; Killer of Sheep, dir. Charles Burnett (New York: Third World Newsreel, 1978), film.

[19] Daughters of the Dust, dir. Julie Dash (New York: Kino International, 1991), film.

[20] Diary of an African Nun, dir. Julie Dash (Los Angeles: UCLA Film & Television Archive, 1977), film.

[21] Alice Walker, In Love and Trouble: Stories of Black Women (New York: Harcourt, 1973), 113.

[22] Ibid., 115.

[23] Eva Darias-Beautell, “Subversion of a Nun in Love and in Trouble,” Atlantis 15, no. 1 (1993): 86.

[24] The Ascent, dir. Larisa Shepitko (Moscow: Mosfilm, 1977), film.

[25] Susan Sontag, “Looking at War,” New Yorker, December 1, 2002.

[26] Tom Birchenough, “Blu-Ray: The Ascent,” Arts Desk, February 23, 2021.

[27] Peter Wilshire, “A Harrowing Exploration of War and the Meaning of Human Existence: The Ascent,” Offscreen, March 2016.

[28] Vagabond, dir. Agnès Varda (Paris: MK2 Diffusion, 1985), film.

[29] Andrea Kleine, “On Agnès Varda’s Vagabond,” Paris Review, July 9, 2018.

[30] Chris Darke, “Vagabond: Freedom and Dirt,” Criterion, January 21, 2008.

[31] Sheila Heti, “An Interview with Agnès Varda,” Believer, October 1, 2009.

[32] Moses K. Tesi, “The State, Politics, and the Struggle for Democracy in Cameroon,” in Post-Colonial Cameroon: Politics, Economy, and Society, ed. Joseph Takougang and Julius A. Amin (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2018), 3.

[33] Chocolat, dir. Claire Denis (Gennevilliers: Caroline Productions, 1988), film.

[34] Cornelia Ruhe, “Beyond Post-Colonialism? From Chocolat to White Material,” in The Films of Claire Denis: Intimacy on the Border, ed. Marjorie Vecchio (New York: I. B. Tauris, 2014), 116.

[35] William A. Vincent, “The Unreal But Visible Line: Difference and Desire for the Other in Chocolat,” Matatu 19, no. 1 (1997): 125.

[36] Monsoon Wedding, dir. Mira Nair (New York: Mirabai Films, 2001), film.

[37] Kaveree Bamzai, “If We Don’t Tell Our Stories No One Else Will,” Rough Cut, September 22, 2016.

[38] Salaam Bombay, dir. Mira Nair (New York: Mirabai Films, 1988), film.

[39] The Headless Woman, dir. Lucrecia Martel (Buenos Aires: Aquafilms, 2008), film.

[40] Stephen G. Rabe, The Killing Zone: The United States Wages Cold War in Latin America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 110, 140.

[41] Phoebe Chen, “Fragments of Lucrecia Martel’s The Headless Woman,” Another Gaze, June 24, 2019.

[42] Emily VanDerWerff, “Portrait of a Lady on Fire Director Céline Sciamma on Her Ravishing Romantic Masterpiece,” Vox, February 19, 2020.

[43] Portrait of a Lady on Fire, dir. Céline Sciamma (Paris: Lilies Films, 2019), film.

[44] Persona, dir. Ingmar Bergman (Stockholm: Svensk Filmindustri, 1966), film. For a side-by-side scene comparison between these two films, see Marcus Pinn, “The School of Persona: Portrait of a Lady on Fire,” Pinnland Empire, January 17, 2020.

[45] Rachel Syme, “Portrait of a Lady on Fire Is More Than a ‘Manifesto on the Female Gaze,’” New Yorker, March 4, 2020.

[46] Barry Lyndon, dir. Stanley Kubrick (London: Hawk Films, 1975), film.

By Shalon van Tine