A Cartoon That Doesn’t Make the Seventies Cartoonish

Released as a Netflix original series in 2015, F Is for Family follows the Murpheys, a fictional working-class suburban family based loosely off the life of comedian Bill Burr.[1] A dark comedy, the show portrays childhood in the 1970s from a realistic perspective without relying on clichéd Seventies tropes like platform shoes or lava lamps.[2] Burr wanted to animate the decade when “you could smack your kid, smoke inside, and bring a gun to the airport.”[3] Animation series with bleak overtones are all the rage, but unlike shows such as BoJack Horseman, which wallows in preachiness and follows self-important characters relatable only to wealthy L.A. elites, or Rick and Morty, which presents a nihilistic message that gets buried in fantastical space-time adventures and parallel universes, F Is for Family is a snapshot of real life—not only as Burr’s childhood, but of the Seventies malaise experienced by real Americans.[4] While the setting and the characters on the show are fictional, they represent actual historical moments, distinguishing the show as unique for its kind by depicting the tangible struggles and sensibilities of the 1970s.

“Come Home When the Street Lights Come On!”

As a retelling of Burr’s childhood, F Is for Family traces the experience of Generation X, those born between the mid-1960s and the early 1980s. Opposite of the helicopter parenting of today, Gen Xers were often “latchkey kids,” children who had to fend for themselves because the parents were rarely home due to divorce or having to work.[5] Because they had to take care of themselves, Gen Xers became highly independent and skeptical toward authority figures, traits that are evident in all three Murphey children. Burr recalls, “When I was a kid, you’d go outside and you and your friends would collectively decide with your kid brains what to do that day. It could be to go play wiffle ball, play with matches, throw rocks in someone’s pool, or have a crabapple fight. Kids were allowed to be kids.”[6]

That Gen Xers were left to their own devices was a reality that stemmed from changing economic and social factors in America beginning in the 1970s. This period marked the time when the economic boom of the postwar years began its decline. Stagflation (the combination of high unemployment rates, high inflation rates, and stagnating wages) forced families to live on credit and take on second jobs to supplement their insufficient funds.[7] Gen X teens often had to work to aid with the family’s financial responsibilities. Women entered into the workplace in large numbers during this time as well, a fact made possible by both the advances in the women’s movement and by the economic conditions requiring families to have a second source of income.[8] By 1973, when F Is for Family begins its story, the concept of both parents working had become commonplace. Even advertisements from that year discuss how “times have changed” as women had begun to “work in industry” and the new women in the workplace were “the best in the business.”[9]

Employment kept parents out of the home, but so did divorce. Between the mid-1960s and the late 1970s, the divorce rate doubled, largely due to increased leniency within divorce law, allowing women to file for divorce without permission from their husbands.[10] In 1969, Ronald Reagan (who was then governor of California) signed the Family Law Act, allowing no-fault divorces where couples could divorce simply because of “irreconcilable differences.”[11] By 1975, over 70 percent of divorce cases were filed by women.[12] Boomer teens dealt with missing father figures, but Gen X teens had to deal with missing fathers and mothers. As one writer has noted, the “where were you when Kennedy was shot” question becomes for Generation X “when did your parents get divorced?”[13]

Frank and Sue (the Murphey parents) are not divorced in the show, but they fight constantly, and avoiding divorce is alluded to frequently. After a particularly tense fight, Maureen (the youngest Murphey child) tells her mother, “Dad said you guys weren’t getting a divorce because you can’t afford it.” In another episode, the dog gets into a canister of chocolate ice cream and lies on the floor panting and ill only to go unnoticed because the parents are not around and too wrapped up in their bickering to realize what is happening within their home. Frank and Sue represent the quintessential absentee parents: both working, frequently fighting, on the verge of divorce, and no time to deal with their kids’ problems. As such, Gen Xers were left alone, with usually no more direction than what Sue yells to her kids: to “come home when the street lights come on.”

Oil, Unions, and the Rust Belt

Besides the theme of Gen X childhood, F Is for Family is principally centered around the state of labor in the 1970s. Frank works for Mohican Airways in the town of Rustvale (an allusion to the Rust Belt). The oil embargo crisis led to higher fuel costs, and that, coupled with poor labor relations, led to an airline strike, which put Frank in a tricky position of having to work between the CEO and his fellow workers. Frank’s boss Pogo tries to persuade him to stop the strike because “a strike could kill the airline—times are tough!” One incident that prompts worker agitation is when a propeller chops off the head of a baggage handler. The CEO mourns the loss—not of the employee, but of the costly airplane part. The CEO later tries to bribe Frank with corporate perks to get him to convince the workers not to strike. The workers do strike, however, and the interactions between the workers, the union leaders, and the bosses make up a good portion of the first season. While Mohican Airways is a fictional airline, the oil embargo and resulting airline strikes were very real, and the Mohican story reflects actual events happening to labor in the 1970s.

In 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) declared an oil embargo on countries who supported Israel during the Arab-Israeli War.[14] Since America supported Israel against Egypt and Syria, the Arab nations struck back by cutting off oil supplies to the United States.[15] Oil prices quadrupled, regular people had to wait in long lines to buy expensive gasoline, and even after the embargo was lifted a year later, oil prices remained high.

The economic issues caused by the oil crisis were exacerbated by the decline of manufacturing in the Rust Belt. Beginning in the late 1960s, free trade agreements around the globe encouraged large companies to shift their businesses abroad. It became cheaper for large industries to produce commodities using foreign labor than it was to manufacture these resources at home.[16] This is referenced in the show when Frank returns a defective television set and the store manager reveals his xenophobia, telling him that they “must’ve got a bad bunch from overseas—those Orientals don’t do good work.”

By 1971, deindustrialization in heavy manufacturing areas like the Rust Belt meant that blue-collar workers were experiencing layoffs in unprecedented numbers. To add to the problem, the 1970s saw a drastic increase in legislative acts that hindered union activity, impairing workers’ ability to effectively manage labor practices and initiate strikes.[17] Not only were manufacturing jobs on the decline due to outsourcing, but new fields were developing, leading to a kind of a technological revolution, where “the titans of the ‘new economy,’ the Microsofts, MCIs, Sprints, Intels, and Time-Warners, were forming, merging, consolidating, growing.”[18]

Overall, industry was changing, labor was changing, and the Seventies marked a period of steep economic decline and uncertainty. When the workers at Mohican Airways decide to strike, their reasonable requests for overtime pay and on-the-job safety requirements were met with vitriol, such as the boss telling the strikers, “You should all be shot!” This reaction was not the stuff of TV exaggeration—most strikes in the 1970s were met with violent opposition. In 1973 (the same year as the fictional Mohican strike), the Brookside Strike by coal miners against the Eastover Coal Company resulted in the mine owners hiring gunmen to shoot at strikers at the picket line and in their homes.[19] All the coal miners wanted were higher wages and medical benefits to cover excessively dangerous working conditions.

The Mohican situation specifically resembles the real-life strikes by the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO). In 1970, PATCO organized a strike to protest unfair federal airline regulations. The government ordered the employees back to work, causing tensions that lasted throughout the 1970s. By 1981, PATCO demanded better pay and working conditions, and even though underhanded government regulations prevented them from going on strike, they decided that going on strike was the only viable option for actual change.[20] Taking a hardline stance, President Reagan gave them two days to end the strike, but when the strike continued into day three, Reagan fired over 11,000 PATCO employees and banned them from ever working another federal job in the future.[21] Considering that these were primarily specially-trained, working-class employees without college educations, most of these workers plummeted into poverty after the ban—a ban that would not be lifted until over a decade later under Bill Clinton’s presidency. After Frank effectively resolves the strike through his careful negotiating, he is unexpectedly fired from his job, and, as if to echo the PATCO strikes, his boss tells him, “I’ll make sure you never work in air travel ever again.”

“Mommy’s Little Hobby”

In addition to blue-collar work, F Is for Family explores the other side of American labor in the 1970s: women in the workforce. Sue, the Murphey matriarch, works as a Plast-a-Ware saleswoman (an allusion to Tupperware) who gets paid in free Plast-a-Ware products. Frank refers to it as “mommy’s little hobby.” “It’s not a hobby,” Sue sighs, “it’s a job.” Eventually, Sue is offered a part-time position as a secretary for the Plast-a-Ware corporate office where she is exposed to a constant stream of sexist jokes from her male bosses. Fed up, Sue begins to tell them off, when her coworker Vivian steps in and lashes back at the men with her own male-directed sexist jokes. The men laugh, and Vivian explains to Sue that women must act like men to make it in the working world. Sue resists the notion, claiming that making those kinds of jokes is not who she is, but Vivian retorts that “‘who I am’ isn’t going to buy you ten cents worth of groceries.” Vivian gives Sue the hard truth: “Those men are all pigs, yes, and you better get past it if you wanna stay here. This is their game and we have to play along.” As Sue realizes Vivian is right and begins to accept her fate, Helen Reddy’s 1971 feminist anthem “I Am Woman, Hear Me Roar” plays as the scene fades out.[22]

During World War II, women were encouraged to take on “men’s jobs” to aid in the war effort from the home front. Despite the fact that women had demonstrated competence in these positions while the men were at war, women were strongly encouraged to return to domestic roles, and many were even terminated from their wartime positions so that men could return to their previously-held jobs.[23] Pervasive (often government-backed) advertising efforts for kitchen appliances and other suburban staples urged women to become consumers rather than laborers.[24] Fairy-tale-ish 1950s television programming, like Leave It to Beaver or Father Knows Best, also contributed to the notion that women are their happiest when they are homemakers, not career women.

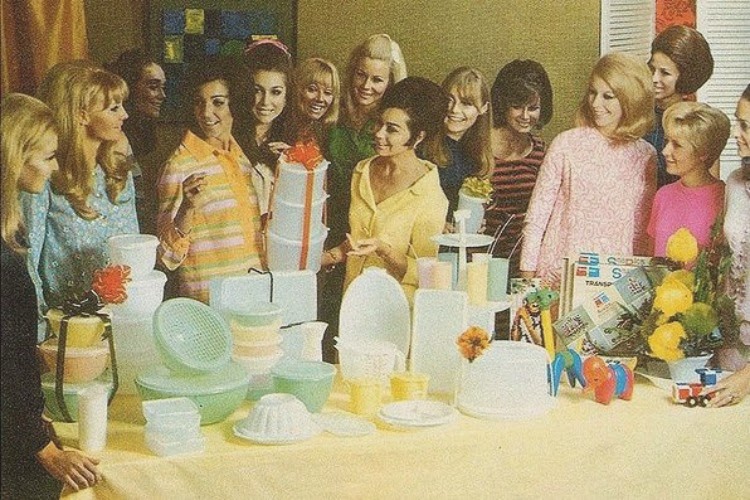

But there was another unexpected connection between the postwar business world and women’s domesticity: plastics. After the war, companies sought to use cheaper materials to cut costs and stimulate postwar profits. The lighter, more flexible polyethylene allowed companies to create versatile products that were unbreakable and could easily be cleaned.[25] Yet, many Americans distrusted this new material, so to sell it, the Tupperware company was born. Tupperware created plastic storage containers marketed to housewives, and they relied on “Tupperware parties,” a direct sales approach where women could test the products in their homes before buying them.[26] Women became the main sellers of the Tupperware product, and that business model allowed women to get a taste of what work was like outside the domestic sphere while still remaining within the domestic sphere.

By 1963, Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique revealed that women were not as content within the home as advertising and television would have Americans believe: women felt dissatisfied with their home life and their marriages, and they yearned for satisfying employment.[27] Fairness in the workplace, then, became a key driver for second-wave feminism. But so was economic reality. By the 1970s, many women had to go to work to support their families, whether they wanted to or not. The largest gain in women participating in the workforce happened between 1970 and 1980—and thus, the increase of women working really took off in the Seventies, not the Sixties, as is often remembered.[28]

It is no surprise that Sue, along with many other women entering the labor force, faced hostile working conditions beginning their careers. In 1973, when Sue begins working for Plast-a-Ware, a report by Mary Rowe, then a professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), was the first to use the term “sexual harassment.” In her report, Rowe described how working women faced a plethora of discrimination and sexual advances within the workplace, and there had not yet been implemented any corrective measures to prevent inappropriate workplace behavior.[29] As more women dealt with difficult work environments, sexual harassment awareness organizations began popping up, dedicated to combating these women-specific issues. For instance, Karen Sauvigne, who co-founded the Working Women’s Institute in 1975, said, “We realized that every single woman…had experienced [sexual harassment] and no one had talked to the other or anyone else about it,” and thus, “the institute…came out of that realization.”[30] Legislative victories also helped make the public aware of women’s work experiences. 1970s court cases such as Williams v. Saxbe, Bundy v. Jackson, and Alexander v. Yale determined that sexual harassment equated to discrimination under the law.[31] Even still, it would not be until 1979 with the publication of feminist scholar Catharine MacKinnon’s book Sexual Harassment of Working Women that the term would get much traction.[32]

Sue’s career encounters are juxtaposed with her daughter Maureen’s unremitting battles against stereotypes regarding what women can and cannot do in the workforce. Maureen is a tomboy and wants to do boyish activities, but Frank habitually tries to force her into “girly” roles, constantly referring to her as “princess” and not allowing her to do anything that he thinks only boys should do. When Maureen wanted to go as an astronaut for Halloween, Frank tells her no because “there are no girl astronauts.” Maureen wants to join the computer club, but Frank insists that she be a part of the Queen Bees instead (a group like the Girl Scouts), despite the fact that Maureen hates it and does not relate to the other girls in the troop. A particularly telling moment is when the teacher accuses Maureen of cheating on her math test because “no girl has ever scored that high.” When it comes to light that she did not cheat but legitimately got the highest grade in the class, she asks her parents, “Now can I join computer club?” Still, Frank attempts to get her to conform to female expectations, such as scolding her when she reads computer magazines. But getting into the computer club was only half the battle. When the club creates a float for the town parade, they relegate her to the role of “space secretary,” assuming that the place for women in technology was the same as it already was in every other field.

Maureen’s experiences mark two major changes for Generation X. First, Gen Xers pushed the boundaries of sex roles by normalizing gender-bending. As a generation who had to adapt quickly to changing economic and social circumstances, Gen Xers developed a chameleon personality trait, where they learned to tone down distinctive features to better blend in rather than stand out (another element of the Gen X “slacker” concept). Rather than accept standard male-female distinctions in dress and attitude, Gen Xers embraced androgyny, the transgressing of gender norms.[33] Gen X men and women began to dress more alike, and Gen X girls were more comfortable with calling themselves tomboys than previous generations: 77 percent of them identified as tomboys in their youth.[34] The popularization of glam rock in the 1970s marked this shift towards androgyny in the music and fashion industries, only to reach its peak in the 1990s with the prevalence of “unisex” fashion and grunge style.[35] Academia began focusing more on the trend, too. For instance, between 1974 and 1985, journal articles that dealt with the topic of androgyny and the blurring of masculine-feminine roles jumped up a whopping 500 percent.[36] And, of course, the press noticed the shift as well: dozens of articles from the 1970s and 1980s commented on the liberating quality of androgyny and the shifting nature of gender roles for the younger generation.[37] “Androgyny is in,” said new wave musician Grace Jones, “and it’s about time.”[38]

The other way that Maureen’s character marks a generational shift is that her career interests point to the budding digital revolution, and further, to the rise of women moving into science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields (STEM). During the 1970s, computing shifted from analog to digital, paving the way toward the current digital age. Personal computers, email systems, video games, and even pocket calculators became available to the wider public.[39] In 1973, the TV Typewriter was introduced, allowing users to type text directly to their television set.[40] Maureen excitedly tries to explain this exact innovation to her neighbor, but her parents shut her down, telling her not to bother anyone with her computer stuff.

Maureen is shown ahead of her time—not just for being interested in computers, but for being a girl interested in computers. Even career women were expected to do “women’s jobs,” but this notion began to change as more women moved into STEM industries and created organizations that promoted visibility in these fields. For instance, in the early 1970s, women researchers founded Women in Science and Engineering (WISE), the Association for Women in Science (AWIS), and the American Physical Society (APS), organizations that encouraged women’s employment and research within the sciences.[41] Part of the problem, however, was that stereotypes about women’s abilities still persisted. Just as Maureen’s teacher had assumed that she cheated on the math test, education professionals continued to debate the reasons why girls traditionally scored lower in math than boys.[42] Because of the long-held perception that the female brain functioned differently, girls were rarely encouraged to participate in math or science-related activities in grade school. As a response, women scientists pushed for educational reforms throughout the 1970s and 1980s, and those campaigns have continued through to the present.

Whether Boomer or Gen Xer, Seventies women had to fight their way into a male-dominated world. The 1970s marked an era for many legislative victories, but there were some symbolic ones too. In 1973, Bobby Riggs challenged professional tennis player Billie Jean King to a “Battle of the Sexes” tennis match, bragging that men were better at sports and that women should be at home “taking care of the babies where they belong.”[43] F Is for Family duplicated this event (but changed the sport to jai alai instead of tennis), and the scene brings together Maureen, Sue, and the other women of the neighborhood in a unified front against male domination of non-domestic spheres. King beat Riggs, giving women proof that the standard stereotypes no longer applied. The victory in the show came at a particularly poignant moment, as both Maureen and Sue had lost confidence in their abilities, but seeing King win the match on TV renewed their spirits and made them secure again in knowing what women can actually achieve.

“Your Bottom Is Six Feet above Our Ceiling!”

Just as F Is for Family highlights women’s experiences in the 1970s, African American struggles are portrayed in a realistic light as well. The show features two key black characters: Rosie, Frank’s co-worker at Mohican Airways, and Smoky, Frank’s boss when he gets the job as a vending machine stocker. Rosie’s experiences at the airline are often contrasted with Frank’s, and while Frank’s experiences are often unfair, Rosie’s are usually slightly worse—and the distinction is typically traced back to his race. When Frank loses his job, he complains to Rosie about hitting rock bottom, but Rosie quickly reminds him: “Your bottom is six feet above our ceiling!” Most of the scenes with Rosie involve him deserving a promotion, but not getting it because he is black. When Pogo yells at two of the white baggage handlers that they have never been promoted because of their laziness, Rosie asks, “and why haven’t I been promoted?” insinuating that discrimination is the only thing that accounts for him remaining in his lower position.

Rosie’s experiences echo the economic realities that many African Americans faced in the 1970s and 1980s. The unemployment rate among blacks compared to whites was double in the 1970s, and by 1983, over 19 percent of African Americans were unemployed compared to 8 percent of whites.[44] More blacks moved into white-collar jobs—an improvement over the 1960s—but they rarely moved up into higher salaried positions as frequently as whites, and their earnings stagnated more than the earnings of white Americans.[45] Later in the show, Frank is promoted and Rosie is expected to take Frank’s old position, but the company gives both positions to Frank (but only pays him for one). Rosie walks out, and Pogo tries to win him back by explaining to him (through pre-written index cards) that the decision “had nothing to do with his race.” When Rosie refuses to return, Pogo gets angry and accuses Rosie of being “uppity,” demonstrating that Pogo’s racism indeed lurked beneath the surface and affected his decision-making in the promotion process.

Whereas Rosie’s character represents economic troubles, Smoky’s character highlights cultural tensions. Frank gets fired and has to lean on Rosie’s help to get another job working under Smoky as a vending machine stocker. On the surface, Smoky’s role is to train Frank how to do the job, but his true role is helping Frank overcome his residual prejudices about the black community. Frank stocks candy in vending machines around town, but he also stocks condoms in the downtown black bar. Frank is not racist by any means, but he is often culturally tone deaf, making frequent comments around black people that show he lacks a certain awareness about the differences in their experiences. When Smoky teaches Frank some tricks of the vending trade and mentions that he learned them “while in prison,” Frank innocently responds, “Oh! You were a prison guard?” in which Smoky sighs, “Frank, you are so white.” This thread runs throughout the background of the show, where African American issues sort of exist behind the main characters, shaping their perspectives indirectly when their worlds collide.

That African American issues remain in the background of the show demonstrates how the Civil Rights movement was not foregrounded in the 1970s the way it was in the 1960s. Rather, in the 1970s, the most visible movement was the Black Power movement, most notably through the Black Panther Party. The television program often playing in the background at the Murphey house is a political talk show called What It Is, hosted by Jim Jeffords. The host’s name is likely a reference to real-life news anchor Jim Jenson, but the show is clearly a humorous homage to William F. Buckley’s political program Firing Line. In one particular episode of What It Is, Jeffords tries to explore “issues facing the black community,” and his guest is Tecumseh X. DuBois, a member of the Black Liberation Alliance for Black Liberation, an organization resembling the Symbionese Liberation Army, a radical organization that existed from 1973 to 1975 (most remembered for the abduction of Patty Hearst).[46] Jeffords typically condescends to his guests, demonstrating his complete lack of cultural awareness, as is evidenced by his introductory question to DuBois: “May I ask, what was wrong with your birth name?”

This particular Jeffords’ show mimics the 1977 Firing Line episode between Buckley and Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver. Buckley begins the show outlining Cleaver’s criminal record, and throughout he tries to undermine Cleaver’s philosophies by making them seem barbaric and violent. Yet, Cleaver calmly cuts back at Buckley, specifically pointing out how the media, especially television programs like Firing Line, perpetuate misconceptions about marginalized experiences and promote capitalist and imperialist ideologies under the guise of balanced programming: “The pigs of the mass media who manipulate information—they distort statistics. They distort reports. Essentially, they distort reality. We define the pigs as those who are actively involved in the machinery of oppression, the three categories of evil: avaricious businessmen, demagogic politicians, and the racist pig cops. These are the pigs of the power structure.”[47]

F Is for Family uses the Jeffords show to validate the kind of claims that Cleaver made about the media. During the 1970s, news networks consolidated into the Big Three commercial networks (ABC, CBS, NBC). To remain competitive with expanding television programming, news media reported sensationalist coverage of events and social problems.[48] This phenomenon was especially true regarding issues related to racism or sexism. One example is seen when Jeffords paints himself black, dresses like a pimp, and hangs out in the seedy part of town to see how white people react to him in an episode titled “To Be Black in America Today.” Another example is when Jeffords interviews women’s rights activists in a panel titled “Feminist Focus,” in which he asks the women, “Have you ladies ever considered that people might take you more seriously if you combed your hair?” As captured so perfectly by the satirical film Network (1976), news media in the 1970s became more like entertainment rather than hard news reporting.[49] When the Black Liberation Alliance holds Mohican Airways hostage, Jeffords covers the affair in a completely slanted and absurd fashion, stating, “If that doesn’t win me a Peabody, I’ll blow a horse.”

“As a Man, I Have to Do Better, or What Am I?”

Arguably the main theme in F Is for Family is the changing nature of masculinity in the 1970s, especially through the perspective of Frank. The introductory sequence shows a young Frank who has just graduated high school, floating through the clouds, happy and carefree. Suddenly, he is smacked in the face with a draft notice, then a baby bottle, and then a wedding cake (note that the baby bottle comes first). His belly grows, his hair recedes, and he becomes bombarded by symbols of adulthood like a comet storm: unpaid bills, broken appliances, kid toys, report cards, flat tires. The opening ends with him in an Archie Bunker-esque armchair surrounded by his family, just like the introduction to Married with Children.

This introduction to the show sums up the frustrations of average American men at this time who had big dreams that were stilted by uncomfortable realities. Frank believes in hard work and feels that the traditional family structure is ideal, but throughout the show, he learns the hard truth that the American dream is a lie. Much of his persona is based around the notion that he must be a “good man”—one who served his country in the Korean War, married his girl when she got pregnant, works a dead-end job to provide for his family, and raises three rowdy kids to stay out of trouble. Yet, Frank’s masculinity is constantly challenged, beginning with him losing his job.

After the strike, Frank is unexpectedly fired, leaving him out of work for weeks. During that time, he becomes depressed and loses his sex drive. In one particularly cringeworthy scene, Sue tries to initiate love-making, but Frank cannot perform, leaving him feeling like less of a man. To drive the point home, the Lou Rawls song “Natural Man,” a song about changing masculinity, plays in the background of the scene.[50] Sue encourages Frank to apply for government assistance, saying that there is “no shame in filing for unemployment.” But Frank is ashamed to file for unemployment because, in his worldview, welfare and government assistance are for lazy people trying to game the system, not hard-working veterans and family men. When he finally steps foot in the unemployment office, he finds himself overwhelmed by the large number of out-of-work people—and his own shame. He sees an acquaintance and pretends to be there on other terms, but his voice is drowned out by everyone in the background: “I need a job.” “I don’t know how I’m gonna eat this week.” Not able to humble himself to file, Frank runs out of the unemployment office and lies to Sue about it the next day.

For the average man in the Seventies, and for most of the twentieth century for that matter, losing his job meant losing his identity. The concept of “being a man” was heavily wrapped up in one’s work and ability to provide for his family. As unemployment grew in the 1970s, the media began to report on the ways it affected men’s psyche and health. “Whenever a man is without work,” noted one reporter, “he is without much more than buying power—his whole life is changed.”[51] Psychologists started to realize the connection between employment and male identity as well, arguing that men not being able to earn an income led to the “disintegration of [one’s] confidence as a man.”[52]

This crisis of male confidence is evident in Frank’s character, especially in the ways that he deals (or does not deal) with Sue picking up the slack. Sue’s career options begin to blossom when Frank’s declines, and this role reversal creates incredible tension between them. Their marriage becomes so strained that they decide to go on a couples counseling retreat. In a moment of harsh honesty, Frank confesses that his masculinity was challenged by Sue’s success, and he admits that he secretly wanted her to fail, saying, “As a man, I have to do better or what am I?”

Frank’s issues with masculinity are often contrasted with his neighbor Vic, a popular sex-drugs-and-rock-n-roll type whose home is always filled with famous people and beautiful women. Vic works as a radio disc jockey, drives sports cars, and consumes large quantities of cocaine. To Frank, Vic represents the hedonism of the counterculture: his money comes from the music industry, he dodged the draft, he womanizes and takes drugs at leisure. Compared to Vic, Frank sees himself as the one grounded in the real world: he served his time in Korea, he works a blue-collar job, he takes care of his family. Yet Vic always gets the breaks: he is popular, throws lots of parties, money and women come easy to him, and—as is alluded to many times in the show—he is blessed with a big package. For Frank, a strong work ethic and family values make up his identity as a man, but unfortunately, Vic’s presence challenges Frank’s long-held conceptions about masculinity since Vic exudes manliness without earning it in the traditional sense.

This crisis of masculinity illustrated in F Is for Family extends to the younger generation as well. Much of Kevin and Bill’s childhood centers on proving their manhood to their peers. Kevin, for instance, almost drowned as a child, so after falling through the ice in the lake, he freaks out, causing his friends to make fun of his unexpected reaction. He spends the next couple episodes trying to prove he is not a wimp. Bill has similar experiences. Throughout the show, Bill is perpetually traumatized by uncomfortable events beyond his control: he walks in on his brother masturbating, he sees his parents have make-up sex, he watches a man’s head get blown off, and he gets an erection at a public swimming pool. Each time he attempts to discuss his embarrassing moments with his father, Frank merely responds by telling him to “push down” his feelings and ignore them because that is what a real man would do.

The tensions between Frank and his sons represent a real generational clash between Gen Xers and their parents. During the 1970s, when early Gen Xers were coming of age, the men’s liberation movement formed in response to the gains made by the women’s movement. This movement called for a change from the traditional masculinity of the past. It opted for a new form of manhood—one that is in touch with the feminine side and rejects the typical aggressiveness, competitiveness, and machismo that had always been associated with manliness.[53] From books to movies, the media picked up on this new form of masculinity, arguing that men who were “more sensitive, more liberated” would live happier and healthier lives.[54] But this movement was merely budding at the time Gen Xers were becoming teenagers, so while they were likely more receptive to these changing norms, they still had to confront the old tropes.

Bill in particular struggles with others undermining his manhood. In many episodes, Bill must stand up to bullies in some form or another. When his sister sticks up for him in an early episode, he is picked on for having a girl do his fighting. Kevin fights for him in another scene, but then punches Bill in the groin for the trouble. Bill’s kind demeanor and desire to avoid conflict leads others to call him a pussy, a common insult to one’s masculinity. His dad calls him a pussy, his nemesis Jimmy calls him a pussy, his sister calls him a pussy, and even his girlfriend calls him a pussy. Eventually, Bill gets fed up with these characterizations and decides to act out saying, “I’m tired of being good—what has that ever gotten me?” When his family refuses to listen to his troubles, he runs away from home, a common Gen X trope. Teens running away from home became a familiar concern for parents in the 1970s and 1980s. As divorce increased and family life became disjointed and toxic, many teens simply left their homes to live on the streets.[55] Bill, like his cohort, resorted to the seemingly only solution available to him—leaving his troubles in the suburbs where they began.

The gay rights movement further challenged traditional notions of masculinity. In 1973, the year the show takes place, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) officially removed homosexuality as a mental disorder, although it was not until 1987 that it was completely eliminated as a “sexual disturbance.”[56] During the 1970s, gay rights activists worked to change common attitudes about sexuality and gender roles, and through their efforts, people who had remained closeted in their homosexuality began to “come out,” and traditional notions of manhood became challenged.[57]

F Is for Family touches on this social shift with the husband and wife characters Greg and Ginny Throater. Ginny is presented as an insufferable character who cannot stop talking about her marital problems, and it becomes clear that these issues stem from the fact that her husband Greg is gay. In a longwinded conversation with Sue, Ginny complains that her marriage problems “began on their honeymoon,” and that she and Greg “had not had sex facing each other in seven years.” When the audience is introduced to Greg, he is shown sneaking around having sex with men in dressing rooms, and his phone number is written on the wall of the bowling alley men’s bathroom. At Pray Away, the couples counseling retreat that Frank and Sue attend, Ginny and Greg are supposed to be representatives of how well the therapy works, but Greg finally gets fed up with Ginny’s denial and admits to her and the rest of the group that he is gay, screaming, “I want dick more than I want world peace!”

The Seventies in Historical Memory

Just as the show touches on some crucial themes of the Seventies, F Is for Family also embeds a good amount of subtle historical material in the background. For instance, Frank’s favorite television program Colt Luger features a gun-toting, hippie-hating Dirty Harry-esque main character who represents an amalgam of the gritty urban police dramas that became popular during the 1970s and 1980s.[58] Similarly, Kevin makes frequent reference to the shift toward progressive rock, and he is surprised when he learns that Vic plays a song on the radio in exchange for drugs, exclaiming that Vic was “compromising the integrity of the music business.” The joke, of course, plays on the way that mainstream music “sold out” in the 1970s, shifting to large arenas under corporate control.[59] And in the background of almost every episode, there is an allusion to some kind of environmental nightmare that existed before the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations kicked in during the early 1970s: kids running behind the DDT truck, Frank telling Bill his excessive sun exposure will give him a “healthy burn,” Sue’s gynecologist blowing cigarette smoke into her vagina during an exam, and the regular mentioning of lead paint, asbestos, and pool chemicals that surround the characters’ everyday lives.[60]

To remember the Seventies has typically been to remember not much of anything. Even before it ended, critics called the Seventies “a Pinto of a decade,” and noted that the Seventies were “a period of non-definition” and “nothing ever to be nostalgic about.”[61] In his autobiography, Irving Howe said, “Try to retrieve the Seventies and memories crumble in one’s hand. The decade itself lacks a distinctive historical flavor.”[62] In celebrating the end of the 1970s, Zonker from Doonesbury lifted his glass and toasted, “To a kidney stone of a decade!”[63]

Yet, these impressions of the Seventies are inaccurate and need amending. As historian Bruce Schulman has noted, the 1970s “transformed American economic and cultural life as much as, if not more than, the revolutions in manners and morals of the 1920s and the 1960s,” and that the decade “reshaped the political landscape more dramatically than the 1930s.”[64] In many ways, the Seventies created contemporary American thought, and in terms of “race relations, religion, family life, politics, and popular culture, the 1970s marked the most significant watershed of U.S. history, the beginning of our own time.”[65]

F Is for Family corrects this historical memory of the Seventies. Rather than depicting the 1970s as uneventful or flush with disco parties, the show portrays real-life events and attitudes that everyday Americans experienced. The shift in social norms and the rise of economic troubles in the show captures the true Seventies malaise, and, hopefully, remedies the common memory about this understudied and underappreciated decade.

Footnotes:

[1] Todd Spangler, “Netflix Orders F Is for Family Animated Comedy Series from Bill Burr,” Variety, October 22, 2014.

[2] F Is for Family, created by Bill Burr (Los Angeles: Loner Productions, 2015), television.

[3] Don Kaplan, “F is for Family Revives Bill Burr’s ’70s Childhood in Animated Netflix Comedy,” New York Daily News, December 14, 2015.

[4] BoJack Horseman, created by Raphael Bob-Waksberg (Beverly Hills: The Tornante Company, 2014), television; Rick and Morty, created by Justin Roiland and Dan Harmon (Atlanta: Williams Street Productions, 2013), television.

[5] Stephen Katz, “Generation X: A Critical Sociological Perspective,” Journal of the American Society on Aging 41, no. 3 (2017): 18.

[6] Kaplan, “F Is for Family Revives.”

[7] Thomas Borstelmann, The 1970s: A New Global History from Civil Rights to Economic Inequality (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 54–56.

[8] George Guilder, “Women in the Work Force,” The Atlantic, September 1986.

[9] “No Two Moms Are Alike,” Jewel Food Store, Chicago Tribune, May 13, 1973, advertisement; “Ever Buy Insurance from a Woman?” New York Life, Time Magazine, May 21, 1973, advertisement.

[10] Stephanie Coontz, Marriage, a History: How Love Conquered Marriage (New York: Penguin Books, 2006), 261–262.

[11] W. Bradford Wilcox, “The Evolution of Divorce,” National Affairs, September 2009.

[12] “Advance Report of Final Divorce Statistics, 1988,” National Center for Health Statistics 39, no. 12 (1991): 11–13.

[13] Susan Gregory Thomas, “The Divorce Generation,” The Wall Street Journal, July 9, 2011, C1–C2.

[14] Charles D. Smith, Palestine and the Arab-Israeli Conflict: A History with Documents (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2012), 329.

[15] Andrew E. Busch, Reagan’s Victory: The Presidential Election of 1980 and the Rise of the Right (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2005), 6.

[16] Jon C. Teaford, Cities of the Heartland: The Rise and Fall of the Industrial Midwest (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993), 221–228.

[17] Jefferson Cowie, Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class (New York: The New Press, 2010), 234.

[18] Gil Troy, Morning in America: How Ronald Reagan Invented the 1980s (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 20.

[19] “13‐Month Strike Is Ended by Kentucky Mine Accord,” The New York Times, August 30, 1974; Fred Harris, “Burning Up People to Make Electricity,” The Atlantic, July 1974; Harlan County, USA, directed by Barbara Kopple (New York: Cinema 5, 1976), film.

[20] Doug Rossinow, The Reagan Era: A History of the 1980s (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015), 86.

[21] Ibid.

[22] “I Am Woman,” written by Helen Reddy, performed by Helen Reddy (Los Angeles: Capitol Records, 1971), song.

[23] Ruth Milkman, “Gender at Work: The Sexual Division of Labor During World War II,” in Women’s America: Refocusing the Past, ed. Linda K. Kerber, et al. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 541–542.

[24] Lynn Spigel, Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 75–89.

[25] Jeffrey L. Meikle, American Plastic: A Cultural History (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1997), 149–152.

[26] Ibid., 171–181.

[27] Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1963), passim.

[28] “Women in the Labor Force: A Databook,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, November 2017.

[29] Mary P. Rowe, “The Saturn Rings Phenomenon,” American Association of University Women, 1973, 14–17.

[30] Nancy P. Condit, “Working Women’s Institute Publicizes Battle Against Sex Harassment,” The Oklahoman, April 8, 1985.

[31] Carrie N. Baker, The Women's Movement Against Sexual Harassment (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 21–22, 49, 57–58, 78.

[32] Catharine A. MacKinnon, Sexual Harassment of Working Women (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), passim.

[33] Bernard Carl Rosen, Masks and Mirrors: Generation X and the Chameleon Personality (Westport: Praeger Publishers, 2001), 104–105.

[34] David Givens, Love Signals: A Practical Field Guide to the Body Language of Courtship (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2005), 165; Betsy Levonian Morgan, “A Three Generational Study of Tomboy Behavior,” Sex Roles 39, no. 10 (1998): 794.

[35] Simon Reynolds, Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and Its Legacy: From the Seventies to the Twenty-First Century (New York: Dey Street Books, 2016), 382–383; Hilary Alexander, “Unisex Revisited or Growing Up in ’90s,” The New York Times, March 17, 1997.

[36] Allan C. Carlson, Family Questions: Reflections on the American Social Crisis (Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 1991), 30.

[37] Carolyn G. Heilbrun, “Androgynous World,” The New York Times, March 19, 1973, 35; Roger Roth, “The Androgynous Man,” New York Times Magazine, February 5, 1984; Ann Rice, “Playing with Gender,” Vogue, November 1983; Lisa Dalby, “Androgyny: Yes Ma’am, A Woman Can Be More Like a Man!” Cosmopolitan, January 1986.

[38] Gioia Diliberto, “Invasion of the Gender Blenders,” People, April 23, 1984.

[39] Paul E. Ceruzzi, Computing: A Concise History (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2012), passim.

[40] Don Lancaster, “TV Typewriter,” Radio-Electronics, September 1973, 1–13.

[41] Laura Micheletti Puaca, Searching for Scientific Womanpower: Technocratic Feminism and the Politics of National Security, 1940–1980 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 152–153.

[42] “Who Is Really Better at Math?” Time Magazine, March 22, 1982, 64.

[43] LeRoy Ashby, With Amusement for All: A History of American Popular Culture since 1830 (Lawrence: University Press of Kentucky, 2006), 431.

[44] Drew DeSilver, “Black Unemployment Rate Is Consistently Twice That of Whites,” Pew Research Center, August 21, 2013.

[45] Diane Nilsen Westcott, “Blacks in the 1970s: Did They Scale the Job Ladder?” Monthly Labor Review, June 1982, 37.

[46] Tim Findley, “Symbionese Liberation Army: The Revolution Was Televised,” Rolling Stone, June 20, 1974; Earl Caldwell, “Symbionese Liberation Army: Terrorism from Left,” The New York Times, February 23, 1974, 62.

[47] “The Education of Eldridge Cleaver,” Firing Line, directed by Warren Steibel (Washington, D.C.: PBS, 1977), television.

[48] Marc Gunther, “The Transformation of Network News: How Profitability Has Moved Networks Out of Hard News,” Nieman Reports, special issue (1999): 21–30.

[49] Network, directed by Sidney Lumet (Beverly Hills: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1976), film.

[50] “Natural Man,” Natural Man, performed by Lou Rawls (Hollywood: MGM Records, 1971), song.

[51] “When ‘Closed’ Sign Goes Up Over a Plant,” U.S. News and World Report, May 21, 1979, 96.

[52] John E. Hesson, “The Hidden Psychological Costs of Unemployment,” Intellect, April 1978, 390.

[53] Deborah S. David and Robert Brannon, eds, The Forty-Nine Percent Majority: The Male Sex Role (Reading: Addison-Wesley, 1976), passim.

[54] Bruce J. Schulman, The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture, Society, and Politics. (Boston: Da Capo Press, 2002), 178.

[55] Marc Leepson, “Missing and Runaway Children,” CQ Press, February 11, 1983.

[56] Neel Burton, “When Homosexuality Stopped Being a Mental Disorder,” Psychology Today, September 18, 2015.

[57] C. J. Pascoe, “Exploring Masculinities: History, Reproduction, Hegemony, and Dislocation,” in Exploring Masculinities: Identity, Inequality, Continuity, and Change, ed. C. J. Pascoe and Tristan Bridges (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 18–19.

[58] Gary R. Edgerton, The Columbia History of American Television (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 259–260, 310, 397; Todd Gitlin, Inside Prime Time (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 313–314.

[59] Chris McDonald, Rush, Rock Music, and the Middle Class: Dreaming in Middletown (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009), 63–65; G. W. Sandy Schaefer, Donald S. Smith, and Michael J. Shellans, Here to Stay: Rock and Roll through the ‘70s, (Phoenix: Gila Publishing Company, 2001), 317–323; David P. Szatmary, Rockin’ in Time: A Social History of Rock-and-Roll (Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2010), 225–226.

[60] “DDT Ban Takes Effect,” US Environmental Protection Agency, December 31, 1972; Norma R. Kelly and Felissa L. Cohen, “Smoking Policies in U.S. Hospitals: Current Status,” Preventative Medicine 8, no. 5 (1979): 557–561; Michael E. Kraft, Environmental Policy and Politics (New York: Routledge, 2018), passim.

[61] Charlie Haas, “Goodbye to the ’70s,” New West, January 29, 1979, 29; Howard Junker, “Who Erased the Seventies,” Esquire, December 1977, 152–153.

[62] Irving Howe, A Margin of Hope: An Intellectual Autobiography (San Diego: Harcourt Publishing, 1982), 328.

[63] George Packer, “The Uses of Division,” The New Yorker, August 11, 2014, 80.

[64] Schulman, The Seventies, xii.

[65] Ibid.

By Shalon van Tine