In 1989, Marc Lépine entered École Polytechnique in Montreal with a rifle and shot 28 people, killing 14 women and then himself.[1] Charging modern women as being “opportunistic,” Lépine reasoned in his suicide note that he had “decided to send the feminists, who have always ruined my life, to their Maker.”[2] Feminists viewed Lépine’s attack as a violent culmination of male resentment toward the feminist movement—a symbol-come-alive signifying the violence women face every day. In response to the shooting, radical feminist Andrea Dworkin encouraged feminists “to be the woman that Marc Lépine wanted to kill” and that women should continue to resist anti-feminist hatred.[3]

Dworkin embraced this moment as a call to arms, but women in other feminist camps viewed Dworkin as more of a reactionary, a representation of the kind of woman who made feminists look like a group of angry, man-hating harpies. Dworkin, along with Catharine MacKinnon and other second-wave feminists, argued that pornography and prostitution equated to violence against women, and that legislation should be implemented to ban pornographic materials.[4] However, not all feminists agreed with this stance, and a newer crop of sex-positive feminists arose out of response to these stifling views. This tension led to the feminist sex wars in the 1980s—debates between anti-pornography feminists and sex-positive feminists—and marked the end of the second-wave reign and the beginning of third-wave feminism.[5]

Feminist Sex Wars of the 1980s

One of the key proponents of third-wave feminism was cultural critic Ellen Willis, who criticized anti-pornography feminists as being strikingly puritanical and conservative, and noted that they had “condemned virtually every variant of sexual expression as anti-feminist.”[6] In her 1981 Village Voice essay “Lust Horizons: Is the Women’s Movement Pro-Sex,” Willis coined the term “pro-sex feminism,” the notion that women’s freedom and sexual preference went hand-in-hand.[7] Despite being on the forefront of a new movement within feminism, Willis was still of the Baby Boomer generation—one that was growing seemingly out of touch with the sensibilities of 1980s youth culture. Because of this disconnect, Generation Xers developed a new branch of feminism—the third wave—which aligned better with their tastes and political experiences.

An important figure of third-wave feminism is Rebecca Walker, daughter of novelist and second-wave feminist Alice Walker. She argued that third-wave feminism was “founded in response to a feeling on college campuses in 1992 that feminism was in some ways dead, irrelevant, that women of my generation were apathetic—not desirous of working on behalf of women’s empowerment.”[8] In response to Anita Hill’s testimony in 1991, which accused Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment, Walker penned an essay in Ms. suggesting that it was time for Generation X to adopt a new form of feminism—one that dealt with issues of sexual harassment by empowering women’s voices:

To be a feminist is to integrate an ideology of equality and female empowerment into the very fiber of my life. It is to search for personal clarity in the midst of systemic destruction, to join in sisterhood with women when often we are divided, to understand power structures with the intention of challenging them. While this may sound simple, it is exactly the kind of stand that many of my peers are unwilling to take. So I write this as a plea to all women, especially the women of my generation: Let Thomas’s confirmation serve to remind you, as it did me, that the fight is far from over. Let this dismissal of a woman’s experience move you to anger. Turn that outrage into political power. Do not vote for them unless they work for us. Do not have sex with them, do not break bread with them, do not nurture them if they don’t prioritize our freedom to control our bodies and our lives. I am not a post-feminism feminist. I am the Third Wave.[9]

For Walker, and for other Generation X women, it was time for a new feminism to take shape.

The manifestations of third-wave feminism were seen most notably in the rise of the Riot Grrrl movement. Riot Grrrl was a punk feminist subculture that began in Olympia, Washington, in the 1990s, although its influences can be traced back to the female innovators in early punk and hip hop. Early women pioneers in music during the 1970s and 1980s helped to pave the way for the women who would shake things up in the 1990s. Patti Smith broke into CBGB’s punk scene as a female poet to be taken seriously—not just another female rock prop. Lester Bangs noted, “Let it never be forgotten that until Patti Smith slashed through the barriers like a henbane banshee in 1975, rock was almost exclusively a male-supremacist world.”[10] Women such as Kim Gordon from Sonic Youth, Exene Cervenka from X, and Alice Bag of the Bags projected a powerful female presence onto the underground rock world dominated by men.[11]

Patti Smith at CBGB's in 1975

One of the most important influences on the Riot Grrrl movement was Poly Styrene from the band X-Ray Spex. Not only did Styrene stand out in the male-dominated British punk scene, but her musical style was sonically experimental, similar to other female-fronted British punk artists like the Slits and the Raincoats.[12] Styrene dealt with feminist issues that were subtler than the traditional second-wave concern for employment and reproductive rights. Instead, she focused on society’s perceptions of women. In the X-Ray Spex song “Art-I-Ficial,” Styrene explores how women’s roles are shaped by societal expectations: “I know I’m artificial, but don’t put the blame on me: I was reared with appliances in a consumer society. When I put on my make-up, the pretty little mask not me. That’s the way a girl should be in a consumer society.”[13]

Poly Styrene from the band X-Ray Spex

The empowered female artists in the hip hop scene were another key influence on the ethos of the Riot Grrrl movement. Like punk, hip hop was also controlled by men, so women rappers not only had to struggle to be taken seriously in the industry, but they faced more resistance when they presented controversial themes. In 1989, Queen Latifah released the album All Hail the Queen, which boasted a collection of politically-topical and feminist-themed tracks, especially her signature song at the time, “Ladies First”: “Some think that we can’t flow. Stereotypes they got to go. I’m gonna mess around and flip the scene into reverse. With what? With a little touch of ladies first.”[14]

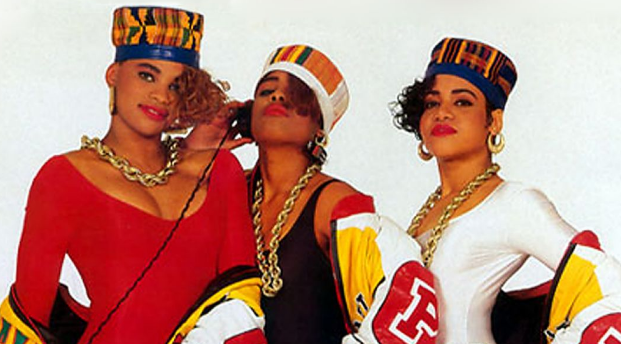

Salt-n-Pepa were another important influence on Generation X’s brand of third-wave feminism in music. Salt-n-Pepa formed in 1985 and consisted of Cheryl “Salt” James, Sandra “Pepa” Denton, and Deidra “DJ Spinderella” Roper. They were the first women rappers to have three albums go platinum, making them one of the most influential groups in hip hop history.[15] In 1990, Salt-n-Pepa released the record Blacks’ Magic that boasted multiple hit singles, such as “Let’s Talk About Sex,” a song that addressed the touchy subject of safe sex in an open and upfront manner, allowing Salt-n-Pepa to reach a large audience about the issue of HIV and AIDS without condemning sexual pleasure.[16] Their song “Independent” confronted the issue of women’s economic dependence on men by making fun of men who are incapable of providing financially.[17] In 1993, the band released the album Very Necessary, and the lyrics and music video for the popular track “Shoop” demonstrated the band’s feminist stance by switching the roles of men and women in rap music, putting the men in the position of the objectified person and the women in the position of sexual power.[18] While both rock and hip hop remained predominately male, these women pioneers shifted the perception of what women could do in the music world.

Salt-n-Pepa

While Riot Grrrl was influenced by these female-fronted bands and feminist philosophies, the movement got its footing more directly as an extension of one band: Bikini Kill. Bikini Kill was a punk band formed by Kathleen Hanna, Tobi Vail, Kathi Wilcox, and Billy Karren. At Evergreen State College, Hanna studied the textual art of Barbara Krueger and Jenny Holzer, along with the feminist literature of Betty Friedan and Kathy Acker.[19] When the college censored her provocative artwork, Hanna opened an art gallery that displayed feminist art and allowed underground bands to play.[20] Hanna did spoken word performances to speak out against sexism and sexual harassment, but worried that her art was not reaching a large enough audience. Seeking guidance from one of her idols, Acker advised her, “No one goes to spoken word shows—you should get in a band.”[21]

In 1989, Hanna took Acker's advice and joined up with friend Toby Vail to create Bikini Kill. Vail had already established herself in the burgeoning independent music scene by playing in the band the Go Team with indie veteran Calvin Johnson (from the band Beat Happening) and releasing cassette tape and vinyl singles on K Records.[22] Vail also had experience publishing zines, starting the underground feminist publication Jigsaw in 1988.[23] Bikini Kill’s music featured the punk style, and its lyrics centered around controversial women’s issues: incest, rape, menstruation, lesbianism, masturbation, and female empowerment.[24] Hanna usually performed in her bra or underwear, often with the word “slut” written on her stomach.[25] The band took third-wave feminism to the stage, embracing their sexuality and not apologizing for it. Hanna noted that they “tried to take feminist stuff we read in books and filtered it through a punk rock lens.”[26]

Bikini Kill

After releasing their second album Pussy Whipped through Kill Rock Stars (the label that would release other Riot Grrrl bands and eventually Nirvana), Bikini Kill’s fan base increased. Yet, with larger numbers of fans, Bikini Kill faced aggressiveness from the men who typically crowded punk shows. At any given punk show, the norm was men at the front in the mosh pit while women remained towards the back holding their jackets, leading to the derogatory term for women at punk shows as being “coat hangers.”[27] This setup enraged Hanna, so it became standard for her to demand that girls come to the front, and men who violated that rule would be scolded by Hanna herself.[28] When Bikini Kill began touring, they handed out leaflets before their shows instructing the following: “At this show, we ask that girls/women stand near the front, by the stage. Please allow/encourage this to happen. This is an experiment.”[29] Unfortunately, some male members of the audience took this request as a threat, and men started attacking women who had placed themselves near the front, which often led Hanna to stop the show mid-set to verbally chastise them. Carrie Brownstein (of the Riot Grrrl band Sleater-Kinney) noted that it was “an empowering and surreal experience because you weren’t really used to being talked to from the stage.”[30]

Riot Grrrl as a more widespread feminist movement began to take shape when Bikini Kill teamed up with the band Bratmobile and moved to Washington, D.C. in 1991. Bratmobile was the musical project of Allison Wolfe and Molly Neuman, both of whom created the feminist zine Girl Germs.[31] Jen Smith, who did artwork for Bratmobile, told the others, “we need to start a girl riot.”[32] Vail suggested changing “girl” to the roaring “grrrl,” and the group started the first zine of the movement: riot grrrl.

Riot Grrrl Zine from 1991

The first Riot Grrrl meeting took place at Positive Force, an activist organization founded by the D.C. punk community in the 1980s, and the meeting included women only so that they could speak freely about issues such as coming out of the closet, experiencing sexual abuse, or confronting violence.[33] The first riot grrrl zine contained a manifesto written by Hanna, but attendees were encouraged to contribute their own interpretations of the movement to the zine as well. The manifesto outlined the philosophies of Riot Grrrl for the new third-wave generation of feminists:

BECAUSE we wanna make it easier for girls to see/ hear each other’s work so that we can share strategies and criticize-applaud each other. BECAUSE we must take over the means of production in order to create our own meanings… BECAUSE we don’t wanna assimilate to someone else’s (boy) standards of what is or isn’t… BECAUSE doing/ reading/ seeing/ hearing cool things that validate and challenge us can help us gain the strength and sense of community that we need in order to figure out how bullshit like racism, able-bodieism, ageism, speciesism, classism, thinism, sexism, anti-Semitism and heterosexism figures in our own lives. BECAUSE we see fostering and supporting girl scenes and girl artists of all kinds as integral to this process. BECAUSE we hate capitalism in all its forms and see our main goal as sharing information and staying alive, instead of making profits of being cool according to traditional standards… BECAUSE we are unwilling to let our real and valid anger be diffused and/ or turned against us via the internalization of sexism as witnessed in girl/ girl jealousism and self-defeating girltype behaviors. BECAUSE I believe with my wholeheartmindbody that girls constitute a revolutionary soul force that can and will change the world for real.[34]

Riot Grrrl meant female creativity, unchecked by society’s patriarchal standards or expectations. It meant embracing the DIY (do it yourself) punk ethic. It meant dismantling the various forms of oppression that kept women down. And most of all, Riot Grrrl meant the freedom to be a girl—free with one’s sexuality, free with one’s thoughts, free from corporate control, and free from violence.

In 1991, K Records hosted the International Pop Underground Convention featuring bands from their label. “Girls Night” was dedicated to women musicians, giving exposure to many of the female bands that would come to define Riot Grrrl: Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, Heavens to Betsy, 7 Year Bitch, and L7.[35] Throughout the early 1990s, more Riot Grrrl bands began popping up: Huggy Bear, Sleater-Kinney, The Frumpies, and Bangs. However, the immense exposure to this new scene arguably led to its demise.

Bikini Kill and Huggy Bear at the International Pop Underground Convention in 1991

As the Riot Grrrl movement gained momentum, the media became intrigued by this new feminist phenomenon of Generation X. The women of Riot Grrrl were portrayed as angry feminazis, girls permanently damaged by sexual abuse, or, worse yet, girls starting a trendy new fad that was all style and no substance. Newsweek called them “a sassy new breed of feminists for the MTV age.”[36] L.A. Weekly called it a girly movement beginning in “pink bedrooms.”[37] And Seventeen dedicated an article to their combat boots, bad haircuts, and other fashion choices.[38] It quickly became clear that the mass media would not accurately portray the true meaning of the movement to the public, so, because of this, many Riot Grrrl bands decided to participate in a media blackout.[39]

The women of Riot Grrrl had hoped the media blackout would allow them to control their own narrative; however, this lack of information allowed the media to manipulate the Riot Grrrl message to the media’s advantage. Soon, any female-fronted band was being hailed as part of the movement, and corporate record labels jumped on the chance to promote festivals like Lilith Fair to women itching for a voice.[40] Female “empowerment” quickly became the easily commodified concept of “girl power”—the notion that anything a woman does makes her empowered, even, and especially, becoming a mindless consumer.[41] The 1990s burst with girl power marketing, used to sell everything from clothing to television. Heavily produced and marketed bands like the Spice Girls and television shows like Sex and the City featured women supposedly empowered by their spending and fashion choices. What began as a subcultural rebellion quickly became commodified rebellion, and the original substance of Riot Grrrl lost its edge.

Mainstream media struggled to define or understand the Riot Grrrl movement.

Despite being short-lived, the Riot Grrrl movement inspired young women to take control of their bodies, their sexuality, and their art. It connected girls from different scenes through its zine networks, and it inspired some of the best music from the 1990s. Most importantly, though, Riot Grrrl helped to spread the new generation’s branch of feminist thought. When Kathleen Hanna was at Evergreen State College, she attended a feminist lecture series featuring second-wave feminist Andrea Dworkin. After hearing Dworkin denounce pornography and sex work, Hanna spoke out about having been a stripper, and how she felt she made the decision of her own free will, and how it was not much different than waitressing. Dworkin dismissed her views as naïve, called Hanna a victim of the patriarchy, and condescendingly told her she would be permanently scarred by her decisions.[42] It was exactly this disconnect between Boomers and Gen Xers that left room for new feminist thought to develop. Riot Grrrl thus became a conduit for third-wave feminism, bringing to the surface a host of new issues that had been ignored by the generation before. Sharon Cheslow (of the D.C. punk band Chalk Circle) noted that second-wave feminism focused more on economic or domestic issues that did not apply to Gen X youth. She noted, “Our main focus was being writers and musicians and filmmakers and artists, and how that impacted our lives, and for us, I think that’s how it was different: it was reclaiming feminism for our lives.”[43]

Footnotes:

[1] “Montreal Gunman Kills 14 Women and Himself,” New York Times, December 7, 1989, 23.

[2] Marc Lépine, “Marc Lépine’s Suicide Note,” School Shooters, July 29, 2014, accessed April 29, 2018, https://schoolshooters.info/.

[3] Julie Bindel, “The Montreal Massacre: Canada’s Feminists Remember,” The Guardian, December 3, 2012.

[4] Estelle Freedman, No Turning Back: The History of Feminism and the Future of Women (New York: Random House, 2002), 207–271.

[5] Jane Gerhard, Desiring Revolution: Second-Wave Feminism and the Rewriting of American Sexual Thought, 1920 to 1982 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 183–195.

[6] Ellen Willis, “Feminism, Moralism, and Pornography,” The Village Voice, October 15, 1979, 8.

[7] Ellen Willis, “Lust Horizons: Is the Women’s Movement Pro-Sex?” In No More Nice Girls: Countercultural Essays (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1992, originally published in The Village Voice, 1981), 3–14.

[8] The Punk Singer, directed by Sini Anderson (New York: Sundance Selects, 2013), film.

[9] Rebecca Walker, “Becoming the Third Wave,” Ms., January 1992, 39–41.

[10] Lester Bangs, “On the Merits of Sexual Repression,” in Main Lines, Blood Feasts, and Bad Taste: A Lester Bangs Reader, ed. by John Morthland (New York: Anchor Books, 2003), 114.

[11] Sarah Marcus, Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2010), 48–49.

[12] Gillian G. Gaar, She’s a Rebel: The History of Women in Rock & Roll (New York: Seal Press, 1992), 200–202.

[13] X-Ray Spex, “Art-I-Ficial,” Germfree Adolescents (Chelmsford: Essex Studios, 1978), record.

[14] Queen Latifah, “Ladies First,” All Hail the Queen (New York: Tommy Boy Records, 1989), record.

[15] The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, ed. Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (New York: Rolling Stone Press, 2001), s.v. “Salt-n-Pepa,” 855.

[16] Salt-n-Pepa, “Let’s Talk About Sex,” Blacks’ Magic, (New York: London Records, 1990).

[17] Tricia Rose, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1994), 151.

[18] Salt-n-Pepa, “Shoop,” Very Necessary (New York: London Records, 1993), record.

[19] Don’t Need You: The Herstory of Riot Grrrl, directed by Kerri Koch (Los Angeles: Urban Cowgirl Productions, 2006), film.

[20] Marcus, Girls to the Front, 35.

[21] Hillary Frey, “Kathleen Hanna’s Fire,” The Nation, December 23, 2002.

[22] Mark Baumgarten, Love Rock Revolution: K Records and the Rise of Independent Music (Seattle: Sasquatch Books, 2012), 215.

[23] Janice Radway, “Girl Zine Networks, Underground Itineraries, and Riot Grrrl History: Making Sense of the Struggle for New Social Forms in the 1990s and Beyond,” Journal of American Studies 50, no. 1 (2016): 7.

[24] See Bikini Kill, Revolution Girl Style Now! (Olympia: Bikini Kill, 1991), record; Bikini Kill, Pussy Whipped (Olympia: Kill Rock Stars, 1993), record.

[25] Farai Chideya, “Revolution, Girl Style.” Newsweek, November 22, 1992, 85.

[26] The Punk Singer, Anderson.

[27] Don’t Need You, Koch.

[28] Marcus, Girls to the Front, 76.

[29] Ibid., 265.

[30] The Punk Singer, Anderson.

[31] Marcus, Girls to the Front, 48–51.

[32] Marisa Meltzer, Girl Power: The Nineties Revolution in Music (New York: Faber and Faber, Inc., 2010), 5.

[33] Grrrl Love and Revolution: Riot Grrrl NYC, directed by Aby Moser (New York: Women Make Movies, 2011), film.

[34] “Riot Grrrl Manifesto,” in The Riot Grrrl Collection, edited by Lisa Darms (New York: Feminist Press at CUNY, 2014), 30.

[35] Gaar, She’s a Rebel, 382.

[36] Chideya, “Revolution,” Newsweek, 84.

[37] “A Movement Begins in a Million Pink Bedrooms,” L.A. Weekly, July, 1992, 10.

[38] Nina Malkin, “It’s a Grrrl Thing,” Seventeen, May, 1993, 80.

[39] The Punk Singer, Anderson.

[40] Jamie L. Huber, “Singing It Out: Riot Grrrls, Lilith Fair, and Feminism,” Kaleidoscope 9, no. 1 (2010): 70.

[41] Andi Zeisler, We Were Feminists Once: From Riot Grrrl to CoverGirl, the Buying and Selling of a Political Movement (New York: Perseus Books, 2016), 173.

[42] Marcus, Girls to the Front, 41–42.

[43] The Punk Singer, Anderson.

By Shalon van Tine